The seminar ‘Financial crisis = political chaos?’ gathered interested citizens, practitioners, journalists, students and academics at the House of Literature in Oslo to discuss what could have been done differently in handling the current financial crisis in Europe. The panelists pointed to the centralisation of power as one of the political consequences of the crisis.

A divided Europe

In the opening note Erik O. Eriksen, ARENA director, emphasized that the crisis has divided Europe and reshaped the political landscape. The rich countries are dictating the poorer ones by imposing an austerity cure to regain the trust of the financial industries.

Blaming and intimidation

Asimina Michailidou, senior researcher at ARENA, discussed the crisis and change in Greece, asking ‘what price for democracy?’ She explained that the ‘fatal blow’ to democratic standards in Greece originates from the way in which the counter-measures to the crisis have been justified to the public. For instance, common tactics include intimidation of the Greek people (‘if we don’t take these measures, chaos will ensue’) and transposing of the blame (and thus the responsibility) for the crisis on society as a whole.

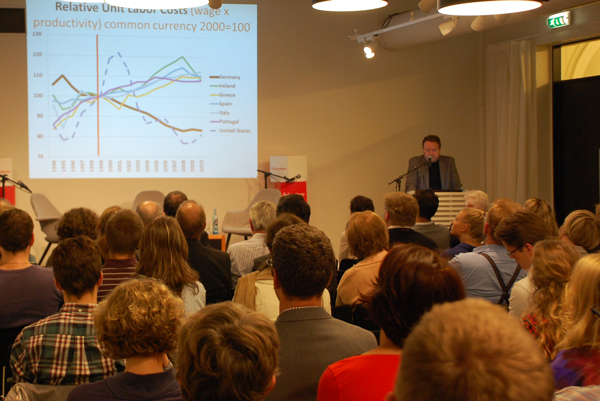

Five overlapping crises

Agustín José Menéndez, professor at the University of León and ARENA emphasized that there are five overlapping crises: economic, financial, fiscal, macroeconomic, and political crises. He claimed that there has been a major change in the EU – introduction of new competencies and centralisation of power to the European Central Bank, European Council and to the Commissioner of Economic and Monetary Affairs. The member states are left with only two leverages to rebalance the economy – labour and tax policy, which in reality translates into reduction of salaries and brings social misery.

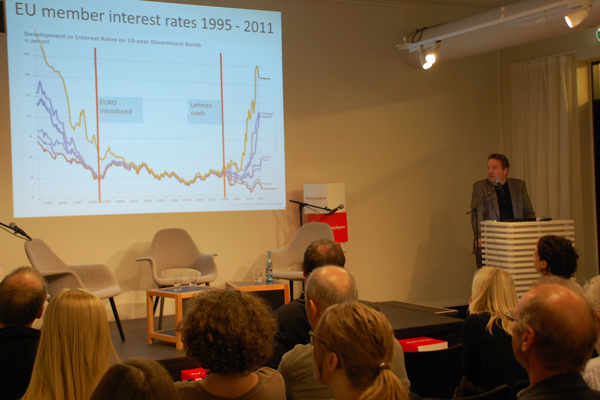

Too much, too soon

Bent Sofus Tranøy, professor at Hedmark University College and Oslo School of Management, noted that there was ‘too much and too soon’ austerity without enough focus on how the cuts should be distributed. This has resulted in an unfortunate effect of reduced demand as those who have the least have been hit hardest by the austerity measures. He remarked that the current Eurocrisis is without precedent, which makes it difficult to draw parallels with previous crises, except perhaps with the Great Depression of the 1930s. He concluded that given the ineffective counter-crisis ‘recipe’ that is currently being followed, it is inevitable that the Euro currency area will undergo reforms and the debts of the weaker members will be further restructured or waived altogether.

Germany’s role

During the discussion several questions were raised regarding Germany’s role. It was pointed out that it is important to the eurozone that Germany remains committed to it. Not only internal factors or dynamics inside the eurozone are important to Germany, but also the global context: Germany is a major exporter. At the same time, Tranøy remarked, the euro crisis is holding the German nominal exchange rate low – if Germany had been outside the eurozone, Germany’s economic strength would have made exports more expensive.

The role of ideas

The panel was also asked to reflect upon the economic philosophy and the role of ideas, including the role of neo-liberalism. Commenting upon the ideological dimension, the panel participants were mainly puzzled by the persistent belief in neo-liberalism and its key component – the conviction that there exist economic rational actors.