Astonishingly, the NSU had operated undetected between 1999 and 2007, carrying out three bomb attacks, two in Cologne, one in Nuremberg, fifteen bank robberies, and ten killings, which took place in seven different German cities. The murder victims, all killed at their place of work, included eight men of ethnic Turkish origin, a Greek citizen, and a female German police officer, shot and killed whilst sitting in her patrol car on a break. Her colleague, severely injured, survived. The NSU stole their guns. The authorities now believe that the NSU could have been operating since 1997, though it was not until January 1998 that they went underground.

The NSU killing spree had ended in 2007 for reasons yet unknown. The group itself dramatically unraveled several years later on 4 November 2011 when two of its three core members, Uwe Mundlos and Uwe Böhnhardt, botched their getaway from a bank robbery in the East German town of Eisenach in Thuringia. A member of the public who spotted the two men reported it to the police. With the authorities closing in on their hideout, rather than face arrest, Mundlos killed Böhnhardt before turning the gun on himself in an apparent murder-suicide pact. Police discovered their bodies in a burned out caravan in which the two men had been hiding. They also discovered the gun used to kill Michèle Kiesewetter, the German police officer the group had murdered in 2007.

The third core NSU member

Zschäpe, the third core NSU member, had shared a home with Mundlos and Böhnhardt in the East German town of Zwickau, 110 miles from Eisenach. Zschäpe acted quickly to destroy incriminating evidence. She set fire to their flat, causing a large explosion, before disappearing. She turned herself in several days later. It was whilst combing through the smoldering ruins of the Zwickau property that the trio had shared that police found a laptop containing a cartoon of the Pink Panther spliced with NSU messages about the killings and footage of the bombings. Before surrendering to police, Zschäpe had mailed DVD copies of this video to several select media outlets, mosques, parties, and an extreme right mail order company. The discovery of the laptop in wreckage of the Zwickau flat together with the handgun used in nine of the ten killings finally saw police connect the dots.

The authorities’ prolonged and embarrassing ignorance of the NSU was even more surprising given that despite functioning as a self-contained, clandestine terrorist cell, the NSU had remained embedded in the German neo-Nazi milieu from which it had emerged. The trio met in the early 1990s in the East German town of Jena where they became involved in the Kameradschaft Jena, a sub-section of the Thüringer Heimatschutz (Thuringian Homeland Protection), a militant neo-Nazi network. They went “underground” in the late 1990s though as one commentator noted “the first thing to understand about the National Socialist Underground is that it was never really underground”. Indeed, other extreme right activists who had known the trio before they began operating clandestinely also knew about the NSU. They raised money for it and provided logistical aid to its three core members. The neo-Nazi rock band Gigi und die braunen Stadtmusikanten also glorified the NSU killings in their 2010 song “Döner-Killer” though given that the phrase “Dönermorde” had already being used in the tabloid press (see below) precisely how much the wider extreme right milieu knew about the NSU has never been conclusively proven.

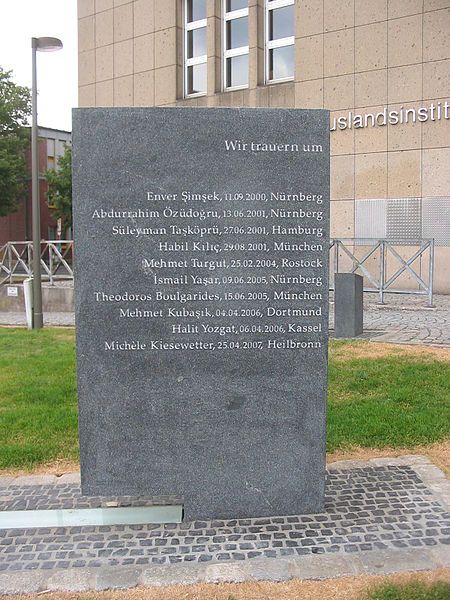

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

To an extent, the trial and verdict reflected this ongoing connectivity. Zschäpe was tried alongside four other defendants who all received prison sentences for their role in aiding the NSU. Ralf Wohlleben, a former spokesman for the extreme right Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (NPD – National Democratic Party of Germany) who had been involved with the NSU trio in the Kameradschaft Jena during the 1990s, had procured a gun and silencer used in some of the killings and was jailed for ten years for aiding and abetting murder. Carsten S., a teenager at the time, received three years for handing the NSU a pistol and silencer used in the killings. André Eminger received two and a half years for helping the NSU – police believe he helped create the NSU video claiming responsibility for their crimes – whilst Holger Gerlach got three years for allowing Uwe Mundlos to use his birth certificate and other ID to obtain fake identities.

Zschäpe spoke only twice during the course of her five year trial in Munich. She had previously denied participation in the murders, portraying herself as a bystander, but conceded “moral” guilt for not doing more to stop the carnage. In her own closing remarks, Zschäpe claimed that neo-Nazi ideas “no longer have any meaning” for her, appealing to the victims’ families that she was a “compassionate person” who was sorry for “the misery that I’ve caused”. The presiding judge, Manfred Götzel, unmoved by her specifying and protestations of innocence, handing her a life sentence on 11 July 2018.

Blind in the right eye?

The NSU case was and is important for what it revealed about the German authorities response to neo-Nazism. News of the group’s existence generated widespread astonishment in Germany and indeed further afield. How had a neo-Nazi terrorist group operated under the radar of the German security services, killing, bombing, and stealing, seemingly with impunity, for nearly a decade? In part, this was due to the attitude of the German police who initially dismissed the killings as the result of an internecine feud within the Turkish criminal underworld, nicknaming them the “Bosphorus-Morde” (“Bosphorus serial murders) in reference to the river flowing through Istanbul. Parts of the German media also wrote the killings off as “Dönermorde” – “kebab murders” – reflecting a negative stereotyping of the victims that underpinned a dismissive media narrative that the murders were the product of immigrant criminality. It was not until 2006 that police profilers began to consider an alternative motive.

Photo: Reclus / Wikimedia Commons

Whilst racist attitudes towards German’s Turkish citizens constitute perhaps one reason that police failed initially to consider a neo-Nazi motive for the crimes, others have pointed to the fragmented nature of Germany’s policing apparatus. There are sixteen different states with sixteen different jurisdictions. This fragmented system may have contributed to a breakdown in intelligence. This is clearly not the whole picture, however. German intelligence has a well-established practice of paying informants (known as “V-Leute”) within the milieu. Indeed, German courts declined to ratify a ban on the NPD in 2003, partly because the government’s case against it rested upon speeches and statements made by individuals who were also paid informants of the intelligence services. Thirty of the top two hundred leaders of the NPD were on the payroll including a former deputy chair and the author of an anti-Semitic diatribe that formed a key part of the government’s evidence.

Given the extent to which the intelligence services had penetrated the neo-Nazi milieu, how was it then that German intelligence failed to learn of the existence of the NSU? Indeed, the killing of Halit Yozgat who the NSU gunned down in an Internet café in Kassel in 2006, was all the more controversial since an informant of the Landesamt für Verfassungsschutz, the Hessian intelligence service, was present during the killing but subsequently claimed not to have seen or heard anything. He had neglected to report his presence at the time of the murder.

The failure of the intelligence agencies to detect the NSU claimed the scalp of Heinz Fromm, head of the Verfassungsschutz (the domestic intelligence agency) who resigned in July 2012. Several other high-ranking intelligence officials also subsequently resigned, or were transferred. The scandal led to nine parliamentary inquiries (one Federal and eight on a state level). The cross-party parliamentary enquiry, whose 1300-page report was published in 2013, highlighted failures “without historical parallel”. It recommended forty-seven reforms aimed at preventing such a recurrence. A second parliamentary enquiry began in November 2015 in order to investigate the group further in light of new information.

The NSU case also led to a major restructuring of Germany’s intelligence architecture through the formation of the Gemeinsames Extremismus- und Terrorismusabwehrzentrum (GETZ - Joint Centre for Countering Extremism and Terrorism), a joint counter-terrorism unit coordinating intelligence on right-wing, left-wing and foreign extremist terrorism, rather than focusing solely upon jihadism. Arguably, these changes were responsible for the subsequent terrorism trials against the Freital Group and the Old School Society.

Unanswered questions

The monumental NSU trial, which began in Munich on 6 May 2013 and took five years to conclude, heard evidence from 540 witnesses and 56 experts. Despite its scale, the trial still leaves plenty of unanswered questions. The court proceedings only briefly examined some of the NSU crimes whilst the bereaved families received no answers from Zschäpe as to how and why the NSU targeted their loved ones, perhaps unsurprisingly given that her defence hinged upon claiming to have only discovered what Mundlos and Böhnhardt had done after their deaths.

There also appears to have been a marked reluctance to probe the nature and extent of the wider NSU support network that might tell us more about how the group was able to maintain its mobility across Germany, which presumably required a level of local knowledge and logistical support to enable it to evade capture. Indeed, the jailing of Zschäpe’s four co-defendants represents only the tip of the iceberg in this respect. Daniel Koehler notes that at least twelve individuals were in “direct contact” with the NSU whilst the German authorities have estimated internally that the NSU support network contained approximately 129 individuals.

The courts and public prosecutor also blocked attempts to investigate the intelligence agencies informers within the NSU orbit and the scandalous decision to shred seven files containing information about informers recruited by the Thuringian Verfassungsshutz the day after news of the NSU’s existence became public. Many families and their lawyers believe that Angela Merkel’s promise of a full and frank inquiry remains unfulfilled.

Zschäpe’s defence lawyer has stated that she will appeal the court’s verdict signaling that the case has not yet perhaps reached its final denouement.

.jpg)

.jpg?alt=listing)