In the aftermath of the January 6, 2021, insurgent attack on the United States Capitol building in Washington DC, the role of active or former military and law enforcement personnel quickly became a major issue of public concern. As of February 23, 2022, researchers have identified at least 140 defendants (ca. 17%) of the January 6 attack with such a background. This overrepresentation of military personnel in particular (according to the United States Census Bureau, around 7% of the population are veterans and another 0.5% active-duty military personnel) caused widespread concern about a potential extreme right infiltration of the military. In addition, some individual case studies of former high-ranking military officers who participated in the January 6 attack became publicly known (e.g. Air Force Lieutenant Colonel ret. Rendall Brock Jr., Army Colonel ret. and information warfare specialist Phil Waldron, or ret. Navy SEAL Adam Newbold). Most recent research has shown that units and branches at least within the military are apparently affected differently. As noted by Jensen et al., the distribution of extremism cases across military branches is highly disproportionate, with the Army and Marine Corps being most prominent.

Special Operation Forces (SOF) and extremist radicalization

Looking at Special Operation Forces (SOF), usually understood to be small elite teams of expert personnel selected, equipped and trained for irregular or unconventional tactics, techniques, and modes of employment, causes for their extreme right radicalization were rarely the focus of researchers before “From Superiority to Supremacy: Exploring the Vulnerability of Military and Police Special Forces to Extreme Right Radicalization” was published in early 2022.

I have explored publicly available inquiry commission reports on extreme right radicalization or significant ethical misconduct (e.g. torture and illegal killings of civilians) by six elite police and military units from four countries (Germany, Canada, Australia, the US):

- In March 1993, two soldiers of the elite Canadian Airborne Regiment tortured and killed a 16-year-old Somali teenager in custody during a peacekeeping operation as the peak of a series of events that in the end left dead a total of four Somalis. In the subsequent string of reporting and parliamentary investigations, numerous links between the Airborne Regiment and various extreme right-wing groups surfaced, such as one soldier’s involvement in the Ku Klux Klan. Further incidents involved airborne soldiers displaying white supremacist tattoos and providing training to the neo-Nazi organization Heritage Front. As a result, the Airborne Regiment was disbanded.

- The case of the Germany military’s (Bundeswehr) elite Commando Special Forces (Kommando Spezialkräfte – KSK), which had one combat company disbanded due to extreme right radicalization in July 2020.

- In November 2019, it became public that officers from a “Spezialeinsatzkommando” (SEK, roughly analogous to a SWAT team in the U.S.) in the state of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania held extreme right views and were connected to militant prepper groups (i.e. persons believing in a catastrophic disaster or emergency to occur in the future and engaging in stockpiling of weapons, food or ammunition in preparation for the downfall of modern societies) of which some members were allegedly involved in plotting terrorist attacks.

- In June 2021, the SEK unit of Frankfurt was disbanded and its 18 active officers suspended after they were found to have been involved in a racist extreme right chat group.

- War crimes committed by Australian SOF personnel in Afghanistan between 2005 and 2016.

- Ethical misconduct by US SOF personnel.

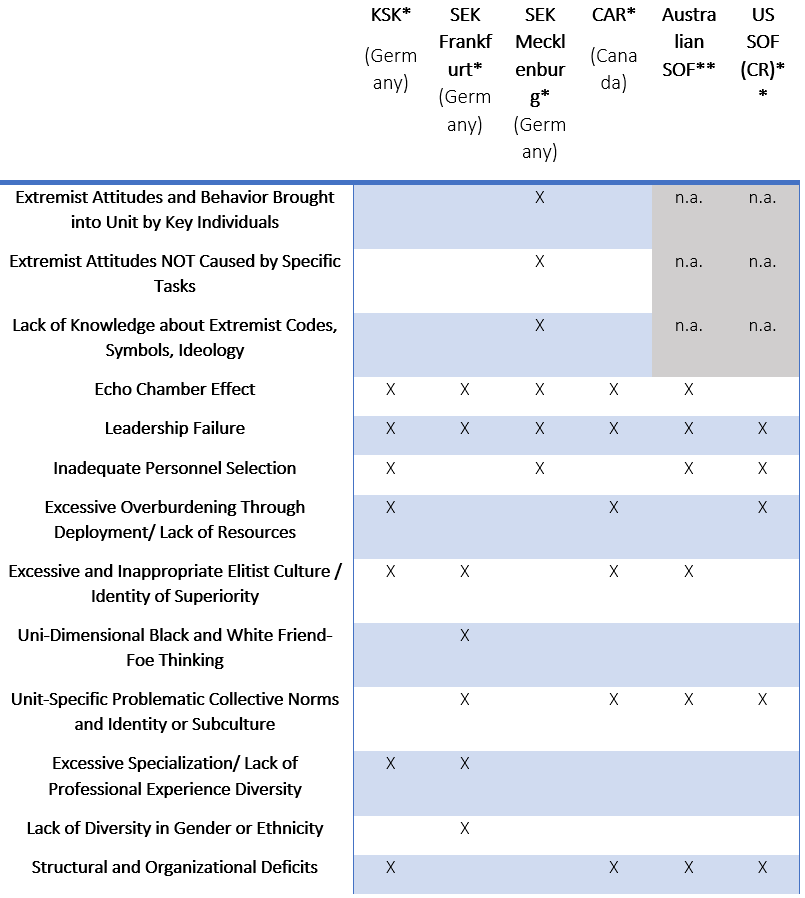

After coding all the available information provided by investigation reports looking at these cases, the following overview matrix provides a first rough indication which factors might be at play when SOF personnel turn to the extreme right:

Table 1: Overview of Inquiry Commissions’ Findings

*Report either specifically focuses on extreme right radicalization or incidents under investigation were in part connected to extreme right motives

**Report focuses on general ethical misconduct, incl. war crimes

Next to general vulnerabilities for radicalization and ethical misconduct (e.g. excessive deployment, leadership failure, poor personnel selection), we can also see risk factors more specific to extreme right radicalization, in particular: lack of diversity in gender and ethnicity, elite warrior subcultures, echo chamber effects and cognitive rigidity. Let’s look at the lack of diversity and the elite warrior subcultures as examples in further detail here.

Lack of Diversity

Western SOF and SWAT units as well as their communities are typically dominated by or exclusively staffed with white men. The extraordinarily high entry requirements and selective screening procedure might risk causing a perception of physical and mental, i.e. natural or biological, superiority over women and ethnic minorities among some SOF and SWAT community members. Similarly, ethnic diversity also appears to be lacking in these milieus, for example among the Navy SEALs. The Army’s enlisted special forces are also 84 percent white. Attitudes towards women in elite units are often informed by notions of heroic masculinity. According to a 2016 RAND study for example, 85 percent of survey participants opposed letting women into their specialties, and 71 percent opposed women in their units. Attitudes of male SWAT members towards female members have rarely been assessed. A 2011 study found that male SWAT members are “somewhat receptive to a woman becoming a team member; however, they are more likely than women to believe that females lack the needed strength and skills”. Toxic masculinity and white chauvinism as facilitators of extreme right radicalization might find fertile ground in elite warrior communities.

Elite Warrior Subcultures

The collective identities and subcultures of SOF and SWAT units are dominated by camaraderie, elitism and distinctiveness from the mainstream community among other values. They could be summarized under the umbrella concept of an “elite warrior or combat culture”, which has been well documented for military SOF and for police SWAT units. SOF and SWAT cultures are based on a selection process that has the function of an initiation rite and includes a high notion of individual agency on the part of the recruit. Passing through the selection process can be described as becoming part of the mythology of exceptionalism that binds together members of these milieus with trust and loyalty.

When this culture changes into an extremist direction, it can form the foundation of a collective identity that emphasizes superiority over all other groups in a given society and the ability or right to disregard rules, regulations, and ethical conventions. In toxic versions of SOF and SWAT cultures, superiority can mutate into supremacy. Informally, the highest status is often given to those members of the SOF community who have the most combat or deployment experience, have shown the least hesitation to engage in often unnecessarily brutal violence, and who have proven to prioritize loyalty to their tribe over official command and control structures even to the point of covering up war crimes and interfering with official investigations. Indeed, this specific version of a warrior identity framed around (biological and cultural supremacy) is almost indistinguishable from the concepts of martyrdom, self-sacrifice, and warrior identity widespread among extreme right milieus. Such a toxic warrior identity and culture can arguably become a bridge between those units and the extreme right.

Conclusion

We urgently need more unit and milieu-specific accounts of the various subcultures within police and military organizations, as well as how they relate to vulnerability to extremist radicalization. Based on my research, however, we can already say that prevention and countering violent extremism (P/CVE) initiatives must be adapted to these subcultures. Raising awareness about the risks posed by extremist radicalization and how to spot such processes within one’s own closest social environment is key. Within SOF communities, emphasis must be placed on P/CVE as essentially investment into more professionalism, resilience, and true superiority over the enemies – abroad or domestic. Fighting off extremist ideologies and radicalization must be understood in these units to be nothing different than prevailing in combat. A positive and strong core collective identity based on democratic plurality and diversity can become a cornerstone of an SOF culture that proactively counters the lure of extremism.

.jpg)

.jpg?alt=listing)