Violent extremism is a complex societal issue that cannot be handled effectively by one profession alone. In the Nordic countries, the prevention of radicalization and violent extremism is based on the assumption that holistic, coordinated, and collaborative approaches are more effective in addressing the plural factors leading to radicalization and violent extremism. This is the multiagency approach, where different authorities and professionals bring their expertise together to solve such complex, ‘wicked problems’.

Between 2018 and 2022, we conducted a Nordic study on policies, perceptions and practices of multiagency approaches to preventing radicalization and violent extremism, funded by NordForsk. Here we will share the main findings.

Design and set-up of multiagency teams

When it comes to the basic set-up of multiagency professional teams at the policy level, the Nordic countries are quite similar. We found that they are all designed to have a governing/executive level and a coordinating/practice level where local actors are given the responsibility to work with clients. However, they differ considerably when it comes to who sits around the table, and to what extent they can share sensitive information about individuals at risk.

We set out to find what the policies said about the main aim of the multiagency teams. These are different, and the aim depends on which country and level of governance you study. All the Nordic countries have multiagency teams that deal with a wide set of problems related to crime prevention. However, in Denmark, on top of more general SSP (School, Social services, Police) collaboration, Infohouse teams are exclusively designed to prevent and handle extremism.

Another element that differs is the legal frameworks for sharing information between institutions. These multiagency teams consist of different professions – for instance a schoolteacher, a social worker, and a police officer – which represent different legal entities, with different regulations, and different professional norms on confidentiality. In other words, what information a professional can share depends on who they represent. There are also considerable differences in regulations on confidentiality between the Nordic countries, and how these regulations are practised – even within the same country.

In Denmark, the Danish Administration of Justice Act (Retsplejeloven §115) enables the police to create structures for crime prevention. The Danish police thus play a key role in organizing collaboration between agencies. In the other Nordic countries, collaboration is coordinated by professionals who are based in other institutions, such as municipalities.

The police legal acts in Denmark and Norway provides a strong mandate to the police on prevention and collaboration, e.g. stating that “prevention is the primary strategy of the police” (Norway). This contrasts with a weaker emphasis on prevention in the police acts of Sweden and Finland, which may explain why the Swedish police are less involved in multiagency collaboration.

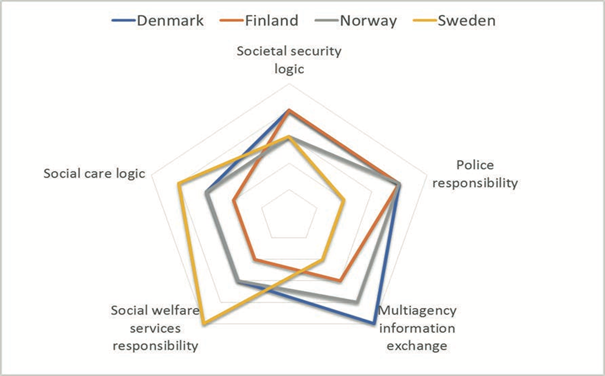

Using organizational theory, we analyzed the designs and set-ups of multiagency collaboration as hybrid organizations which draw upon different institutional logics. Based on a systematic analysis of policy documents, the main institutional logics reflected in policies in the Nordic countries are social care and societal security logic, both strongly tied to preventing violent extremism. Sweden differs from the other Nordic countries, with a weaker involvement of the police, a stronger emphasis on the role of social welfare services and social care logic, and more restrictive norms on exchanging information.

Using surveys among schoolteachers, social workers, and police officers in the four countries we show that these institutional logics are also present among professionals. As expected, police officers are found to be closer to a social security understanding of PVE while schoolteachers and social workers are closer to a social care logic Accordingly, team members bring a variety of perspectives on violent extremism, and different views of what needs to be prevented, how it is handled best, and by whom. There is nevertheless a considerable overlap in shared understandings, especially among those who have personal experience from multiagency collaboration.

Illustration by Jennie Sivenbring & Robin Malmros

Perceptions and legitimacy

We wanted to explore the relationship between perceptions of multiagency collaboration to prevent violent extremism, and the willingness to report concerns of radicalization among the public. To explore this relationship, we used large-scale surveys with nationally representative samples from all four countries. In addition, we fielded surveys to samples of professionals, including police officers, social workers, and teachers, to explore the distribution of perceptions of PVE (i.e. institutional logics), and how these perceptions affect willingness to collaborate across institutional boundaries, and create trust across professions. Some of the main findings are:

Citizens in all countries perceived national PVE policies as quite legitimate, while they hold more mixed attitudes towards reporting concerns of radicalization to authorities.

High perceived policy legitimacy leads to positive attitudes towards reporting concerns to authorities. In other words, the more legitimate citizens view PVE policies, the more willing they are to report concerns. We demonstrate this using an experiment embedded in the surveys. Additionally, the higher institutional trust and perceived procedural justice, the higher legitimacy of PVE policies.

Using spatial analysis, we show the existence of ‘hot spots’ in Nordic cities. These are neighborhoods in cities where there is a combination of higher perceived problems of radicalization, and lower willingness to report among residents. This combination is positively related to the presence of other community problems, and negatively related to institutional trust.

When it comes to professionals, we found that positive perceptions of national PVE policies affects willingness to engage in multiagency collaboration. We demonstrate this using an experiment embedded in the surveys.

We explored degrees of the two institutional logics – social care and societal security – that these professionals hold towards PVE. Contrary to what many would assume on the basis of national policy differences, most of them identified with a social care logic to PVE across professions, including the police.

Professionals with experience in multiagency collaboration express a higher degree of social care logic than peers without experience.

The more similar the professionals are in their conception of approaching PVE, the more they trust each other.

Practices in Nordic cities

Until now we have discussed the policy level and the perception level through surveys fielded with the general public, and professional groups involved in PVE. But how do these teams work in practice in different Nordic cities? To answer this, we followed teams in 13 cities, three in each country (plus one additional team in Norway which served as a pilot case). These were larger or medium-sized cities that all had experience with PVE, and had dedicated multiagency teams. Real cases of radicalization and violent extremism, and the sensitive information that goes along with those, are a delicate matter. Therefore, we had the actual multiagency teams engage in meeting simulations, in which they were asked to deal with two fictive cases constructed by us researchers, and apply their normal working proceedings. In this way we were able to study collaboration in practice, and obtain comparable data (all teams worked on the same fictive cases), while avoiding access to sensitive information. Furthermore, we conducted group and individual interviews with all professionals involved. Some key findings include:

Aside from Denmark, the multiagency teams at the city-level within the other countries have different organizational setups. Some meet only in case of emergencies, others meet regularly. Some hold leadership positions, others are frontline professionals. Denmark was the only Nordic country with a streamlined approach across the country, called ‘Infohouses’.

The factors that shape assessments of concerns and perceptions of risk in specific cases – what is considered ‘a risk’ and why – depends on which institutional logic is dominant in that setting. This influences internal power hierarchies, the choice of risk assessment tools, and with that the negotiations over whether a concern constitutes a risk. In Sweden, the social services sit at the head of the table, call meetings, and are the first to screen referred cases. In Denmark, the police have the overall coordinating responsibility and prescreen referred cases in terms of immediate risks. Norway and Finland are somewhere in between these positions.

There is considerable variation between the countries – and even between different municipalities within the same country – on how multiagency collaboration and information-sharing is practised. Among practitioners in Norway in particular, there are uncertainties as to what extent they can share sensitive information on individuals of concern with partners from other agencies. Information-sharing is mostly based on consent (from the individual or parents), but sometimes also personal trust between practitioners, stretching the rules for a good purpose. By contrast, Denmark has a legal provision that facilitates the exchange of information between agencies for preventative purposes under specific conditions – a cornerstone of Danish multiagency collaboration. Although Sweden has quite similar legal options, information exchange is practised far more restrictively, especially towards the police. However, there are ongoing moves to loosen these rules.

We found that trust plays an important role in enabling collaboration. The professionals spoke of trust at three levels, namely at a 1) structural 2) professional and 3) personal level. These levels are interconnected, but they represent different layers of trust that may be divergent or complementary. At a structural level, general trust in institutions, including their own, infuse a high level of trust between practitioners. At the professional level, understanding limits and regulations, mandates and roles of the other agencies will reinforce existing trust in collaboration and enabling good teamwork. At a personal level trust is enabled through familiarity, and the creation of a safe space to speak about concerns, without fear of misinterpretation.

Conclusion

Though the Nordic countries have all accepted the idea of multiagency collaboration, policies and practices diverge. These are our key notes about good practices:

- Smoother running multiagency collaboration is facilitated by legislation which provides the involved actors with possibilities to exchange information about individuals and groups who are at risk of endangering their own and others’ safety.

- Although there are pockets of mistrust in the Nordic cities when it comes to PVE, such as the aforementioned local ‘hot spots’, the overall finding of high level of trust from both professionals and the public is an advantage for these types of collaboration.

- Insights into the institutional logics behind the policy design and practices of PVE cases enable a better understanding of how ‘wicked problems’ are handled and negotiated.

.jpg)

.jpg?alt=listing)