Despite great progress on the gender equality front, women still earn less than men. A new, comprehensive study of 15 countries in Europe, Asia and North America also reveals significant wage disparities between women and men in the same job at the same employer.

“Previous research has often explained the wage gap between women and men by the fact that they work in different occupations. The spotlight has thus been on how women and men are sorted into jobs with different wage levels,” says Are Skeie Hermansen.

Hermansen is an associate professor at the Department of Sociology and Human Geography and one of the contributors to the study on wage disparities published in the renowned journal Nature Human Behaviour. The study was led by Andrew Penner of the University of California at Irvine, and together with Trond Petersen of the University of California at Berkeley, Hermansen has been responsible for the Norwegian contribution.

“In all 15 countries in the study, we find that wage disparities between men and women in the same job are a significant cause of gender inequality in pay,” he says.

Higher than previously assumed

On average, within-job inequality account for about 50 percent of the total pay gaps across the 15 countries in the study. This is new knowledge and a considerably higher within-job share than previously assumed, according to Hermansen.

“The gender disparities at the job level are thus due to the fact that women receive unequal pay for equal work,” he says

In Norway, wage inequality between men and women in the same job explains 35 to 40 percent of the total gender gap, according to Hermansen. The remaining 60-65 percent is due to gender segregation in the labour market, i.e., women and men receive different wages because they do different work.

“Among other things, women are overrepresented in occupations doing care work in the public sector. Wages are often lower here than in some professions in the private sector where men are overrepresented.”

New data from a variety of countries

In the study, a large international research group calculated the average disparities in wages between men and women with the same level of education and full- or part-time positions. The researchers also examined the wage disparities between men and women who have the same profession, workplace and, finally, the same job.

“For example, we compare wage gaps between male and female lawyers in a specific law firm in Oslo, or gender disparities between kindergarten teachers at a kindergarten in Molde,” explains Hermansen.

The researchers have looked at gender disparities in both total annual earnings and contractual hourly wages. The latter says something about how much the employer pays for a given amount of performed work. All analyses in the study adjusted for gender disparities in education, age, and whether the worker was employed in a full-time or part-time position.

“We’ve used extensive data from a large number of countries that have not previously been used for research. Influential studies of gender disparities in wages at the job level, from Norway, Sweden and the United States, have been based on data from the 80s and 90s,” says Hermansen.

Norway is one of the few countries where data that can identify colleagues at the same employer has long been available for research purposes.

“In many countries, it is only in recent years that researchers have been able to use such data.”

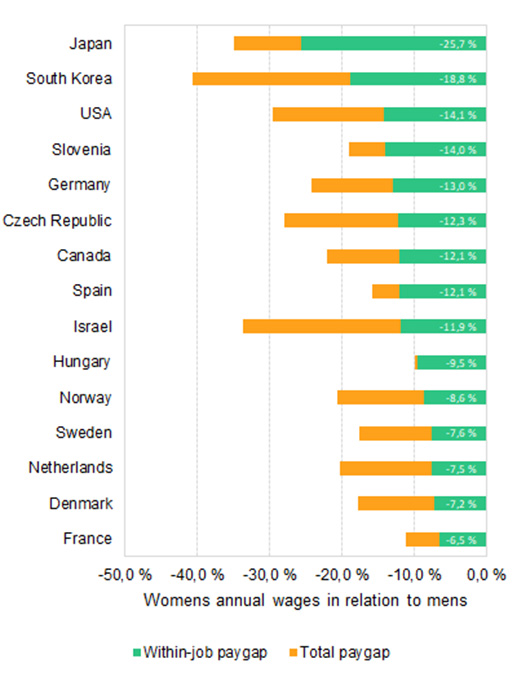

In the study, Norway has the fifth-smallest gender disparities

Here are the main findings from the study with regard to annual wages:

- The greatest overall wage disparities between women and men are found in South Korea (41 percent), Japan (35 percent), the United States (30 percent), Israel (34 percent) and the Czech Republic (28 percent). In Norway, the total gender disparity in annual wages is just over 20 percent.

- Of the 15 countries included in the study, Norway has the fifth-smallest gender disparity (8.6 percent) in annual wages at the job level, after France (6.5 percent), Denmark (7.2 percent), the Netherlands (7.5 percent), and Sweden (7.6 percent).

As regards hourly wages, the gender disparities are generally smaller, but the overall pattern is similar:

- The researchers found the highest overall gender disparities in Japan (32 percent), South Korea (28 percent), Israel (25 percent) and the Czech Republic (23 percent). In Norway, the overall gender disparity is 13.7 percent.

- At the job level, the gender disparities in hourly wages are lowest in Sweden (3.5 percent), Norway (4.6 percent) and Denmark (6.3 percent), along with the Netherlands (4.4 percent).

“Our study does not seek to explain the differences between countries, but primarily to map wage disparities at the job level against segregation in the labour market,” says Hermansen.

“However, we know that important factors advancing equal pay in Norway include strong equal opportunity legislation and a good family policy that facilitates career development among working women with breadwinner responsibilities.”

The wage gap narrowed from 25 to 20 percent

The study establishes that men and women in Norway have more equal pay today than they did twenty years ago. The development has gone in the same direction for all the countries in the survey, except in the three former Eastern Bloc countries of Hungary, Slovenia and the Czech Republic.

Based on annual wages, the gender gap in Norway has narrowed from 25 percent in 1997 to 20 percent in 2018. At the job level, the disparity in men’s and women’s average hourly wages has decreased from 15 to between 8 and 9 percentage points in the same period.

Hermansen believes an important part of the explanation is that an increasing number of women are pursuing higher education.

“Since the mid-80s, women have been overrepresented in higher education. Higher education qualifies people for higher-income jobs,” he notes.

At the same time, Hermansen points out that women, on average, tend to choose fields of study that often yield lower economic returns in the long run.

“That’s why the development is slower than you might expect,” he says.

According to Hermansen, a comprehensive family policies in the form of, among other things, high coverage for kindergarten, probably contribute to reduced overall pay gaps in Norway.

“If we look at differences among women, the wage disparities between mothers and comparable women without children responsibilities have fallen sharply since 2000.”

Wage negotiations and breadwinner responsibilites

Despite the fact that equal opportunity is moving in the right direction, Norwegian men earn an average of 4.6 percent more in hourly wages than Norwegian women in the same position.

“Our study shows that the gap is larger than previously assumed,” says Are Skeie Hermansen.

However, he points out that previous Norwegian studies of gender disparities at the job level used data for a smaller segment of the labour market. The new study covers all workplaces in both the public and private sectors.

“We don’t really know what happens in workplaces where men are paid more than women for doing the same job. There’s probably limited blatant and direct wage discrimination in Norway,” he says.

Hermansen believes that various biases related to individual wage negotiations can contribute to higher gender inequality, and refers to previous research showing that wage disparities are often greater between men and women in higher-paid professions.

“Individual wage negotiations can create room for greater gender disparities. Employers may also facilitate different work responsibilities that lead to different career paths within companies,” elaborates Hermansen.

The gender disparities are generally also considerably larger between fathers and mothers, than among childless men and women.

“Men and women may make different career adjustments, based on the division of labour at home, which can have long-term consequences. However, we did not have data on whether and how may children that men and women had in all the countries, so this was not the primary focus of the present study.”

More research is needed

The figures now presented by Are Skeie Hermansen and the rest of the research group are based on the average gap in wages between women and men for the entire labour market. Hermansen points out that the disparities will be smaller in some workplaces, for example in the public sector. On the contrary, in other parts of the labour market, the wage gap between women and men is wider.

Hermansen is interested in investigating possible explanations for why some workplaces are better at ensuring equal pay than others.

“One important hypothesis is that more bureaucratic organisations, in which there is less room for individual wage negotiations, may contribute to less inequality between different groups in the workplace, including women and men,” he says.

“It’s also likely that increased transparency in wage-setting and highlighting employers’ local accountability can have a positive impact.”

As a result, jobs in the public sector and larger companies in the private sector more often have more equal wages.

“But we don’t really know enough about how these mechanisms work. More research is needed here,” says Hermansen.

“We’re already working on the next step: Investigating what characterises the workplaces that are good or bad at facilitating equal pay for equal work, and whether the same factors explain the equal pay variation between workplaces in different countries.”