Torben M. Andersen, Department of Economics, University of Aarhus

Introduction

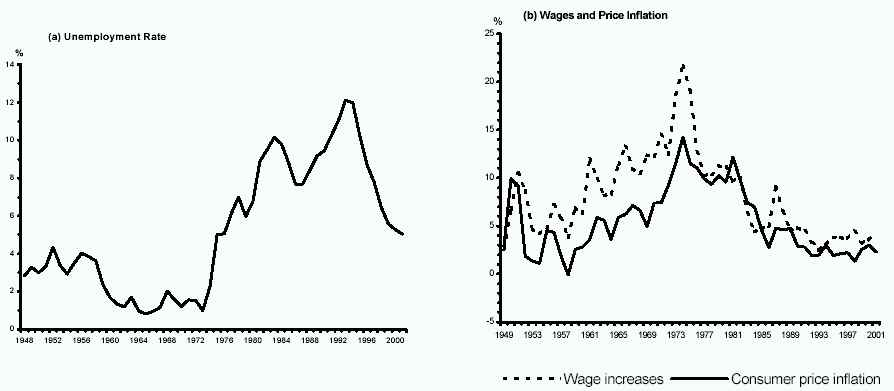

During the 1990s the Danish labour market has been through a remarkable development with a substantial drop in unemployment and moderate wage increases, but also some tendency towards more wage dispersion (albeit from a low initial level). Figure 1 shows the development in the unemployment rate and wage increases. Note that although wage increases during the 1990s have been on the high side seen in European perspective neither nominal nor real wage increases have responded strongly to the sharp reduction in unemployment. This is not a simple story of wage moderation (movement down a stationary labour demand relation) since growth in labour productivity increases has been as high during the 1990s as during the 1980s.

The 1990s has also seen important changes in the institutional structure of the labour market with a shift from centralized towards more decentralized bargaining structures. Calmfors et al. (2001) report an index[20] for centralization/coordination of the bargaining system taking both horizontal and vertical elements into account and find that it has dropped from 0.64 for the period 1973-77, to 0.47 for 1983-87 and 0.34 for 1993-97.

The same period has also seen a shift in labour market policies from a passive policy focussing on income maintenance for unemployed towards a more active policy stressing active job search and creation. An open question is to what extent these changes can account for the changes in labour market performance during the 1990s and in particular through what mechanisms. The present paper takes a closer look at the decentralization process.

By organized, centralized or coordinated decentralization is usually understood a decentralization process where some central control or coherence is maintained as opposed to a decentralization process induced by deregulation and disorganization leading to an individualized labour market. With a centralized decentralization collective arrangements retain their role as regulators of labour market conditions, but the decision making process has become more decentralized. This distinction is important since centralized bargaining has traditionally been seen as part of an – implicit or explicit – social pact allowing the development of an extended welfare state without jeopardizing labour market performance in open economies.

In the Danish case the traditional approach to regulation of labour markets has been based on voluntarily negotiated arrangements between parties in the labour market. Collective regulation rather than formal legal regulations have in this way been the core of the so-called “Danish labour market model”. Political interventions have been seen when collective bargaining has failed, but usually the intervention has been based on the (implicit) compromise advanced by the official conciliator. However, since labour market developments also depend on social- and labour market policies, and fear of political intervention may have disciplined labour market parties, it is a difficult task to disentangle the role of collectively bargained arrangements and political control.

A call for decentralization of labour markets has been motivated by international integration and technological changes requiring more flexibility and adaptation to local/sector/firm specific conditions which it can be hard to ensure in a more centralized system. Representatives for employers have therefore been advocating more decentralization and been instrumental in the development which has taken place[21].

This paper lays out the changes in labour market bargaining, which have taken place in Denmark primarily during the 1990s, and considers whether there is any evidence that it has changed labour market performance.

Bargaining during the 1990s

The Danish labour market is highly organized with almost 80% of all workers being member of a union, and 77% of all employed in the private sector are being covered by a collective agreement[22] (100% in the public sector).

Bargaining used to be highly centralized, but during the 1980s, there has been a trend towards more decentralized bargaining. While some changes towards decentralization were observed during the 1980s, the pivotal change came in 1989 with sector specific negotiations between DI (member organization of employers federation (DA) organising firms in the manufacturing sector) and CO-metal (a bargaining conglomerate representing unions’ organising workers employed in DI-firms). Subsequently, decentralization has been extended to other areas.

The decentralization process has involved changes in both the horizontal and vertical dimension. In the horizontal dimension general negotiations for the larger part of the labour market (the LO/DA area) have been replaced by sector specific bargaining. In the late 1990s the previous synchronization of bargaining at 2-year intervals has been replaced by a less synchronized structure and differences in contract length (3 and 4 years). In the vertical dimension collective agreements increasingly stipulate only general conditions (working hours, rules for flexible working hours, minimal wages etc.) leaving wage settlement to local negotiations. Note that changes in working conditions also have to be approved at the local level to be implemented.

There are some key aspects related to labour market negotiations, which imply that some centralization is maintained despite the decentralized structure of negotiations. First, the right to call a conflict has not been delegated, that is, the conflict threat cannot be directly applied at the local level, but needs to be coordinated/approved at the central level. Secondly, members of the employers’ federation (DA) cannot enter collective agreements without having obtained prior consent of the board of the federation. Finally, the official conciliator maintains a central role in settling bargaining when the parties cannot reach an agreement by themselves. The official conciliator still has the right to bundle different bargaining areas when calling a ballot on the compromise proposal for a collective agreement.

All of the above-mentioned factors effectively mean some central control over decentralized outcomes. However, the trend towards fewer synchronized wage negotiations has broken the centralized aspect following from key groups setting the tune in the wage determination process, with other groups following the agreements made by the first mover fairly closely. At present it is unclear whether the centralized aspects will be maintained or it will be further weakened. At the negotiations in 2000 four-year agreements were made for the private labour market paving the way for a return to a more synchronized system.

Previously, negotiations included general demands settled at the central level (including issues like general pay increases, working hours etc.) leaving more specific demands to subsequent negotiations at the decentralized level. Currently, the central negotiations lay out the framework for negotiations (including dates for exchange of demands, their specificity and topics to be included in such demands), while the specific contents was settled in decentralized negotiations between the member organizations of LO and DA.

With the increased decentralization of wage formation it is natural that there have been changes in wage systems in the labour market in the sense that more workers are now employed under a wage system allowing local and individual variations in wages and less work under the traditional wage system implying a centrally stipulated wage. The standard wage system in Denmark has been the so-called standard pay system (“normallønssystem”), which fixed the wage for different categories of workers in the labour market for the contract period. Historically, this system has dominated the labour market for unskilled workers. Another wage system called the minimum wage system[23] (“minimallønssystemet”) stipulates minimum pay but makes room for personal allowances usually determined on a group basis and related to observable facts like job functions, experience, qualification etc. Recently the minimum pay system (mindstebetalingssystemet) has been introduced and it basically leaves the wage for local negotiation between the employer and employee subject to some minimum levels.

Table 2 shows the development in the use of the various wage systems during the 1990s and there is a clear trend towards the use of wage systems allowing for more flexible and decentralized wage determination. Note that central bargaining still determines the wage for workers on the standard wage contract. In the past there has also been some local elements in wage determination (under the minimum wage system) showing up in the form of wage drift.

|

Contract form

|

1989

|

1991

|

1993

|

1995

|

1997

|

2000

|

|

Standard wage

|

34

|

19

|

16

|

16

|

16

|

15

|

|

Minimal wage

|

32

|

37

|

13

|

12

|

21

|

23

|

|

Minimum pay

|

30

|

40

|

67

|

61

|

46

|

42

|

|

No fixed wage rate

|

4

|

4

|

4

|

11

|

17

|

20

|

|

Sum

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

An important trend in the outcome of negotiations during the 1990s is that they leave room for more flexible working rules. In 1993 23% of workers had a collective agreement, which did not allow any flexibility in working hours, and 77% could have some variation within periods of length up to 3 months (meaning that total working hours over a 3-month period could not vary). In 1998 90% of the workers had a collective agreement allowing variations within a period of 12 months or more (see Dansk Arbejdsgiverforening 1999). It is possible that this development should be seen as an integral part of the decentralization process, since it allows the joint determination of work conditions and wages.

Structural changes

This section considers the available evidence on the importance of the decentralization that has taken place in the Danish labour market. Most of the evidence is indirect since it is difficult to measure decentralization sufficiently precisely for inclusion in quantitative analysis, and since the effects of decentralization in most cases show up by changing the way in which various variables interact.

A striking fact of the labour market development during the 1990s is the fairly large drop in unemployment, which has been taking place without inducing a strong wage hike. Seen in the perspective of historical experiences of the relation between wage increases and unemployment, the latter part of the 1990s has been unique, cf figure 2. Wage equations have systematically over predicted wage increases by a wide margin, and reestimations including new observations have led to a reduction of the coefficient to the unemployment rate (see e.g. Bocian et al. (1999)). This is a strong indication that a structural break has taken place in the wage formation process.

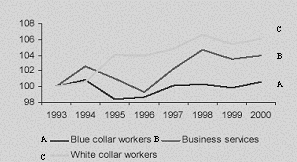

Another noteworthy feature of the development during the 1990s is an increase in wage dispersion for workers with job functions at a high and intermediate level within firms, and also within business services, while no increases in wage dispersion have been observed among ordinary workers, cf. figure 2.

With a move from centralized towards a more decentralized system of wage determination it is natural to expect that firm specific factors come to play a larger role for wage formation. The Danish labour market has historically been characterized by a fairly equal wage distribution, and therefore firm specific factors have previously played a minor role (although firm variations in wages have existed). Bingley and Westergaard-Nielsen (2002) include tenure in estimations of individual wage equations including standard explanatory variables, and use the estimated coefficient to construct a measure of the return to firm specific human capital. While the return to firm specific human capital is moderate, it is found that it has been increasing in recent years[24]. One interpretation is that this is the outcome of the decentralization process making it possible for firms to use wage incentives to protect investments in firm specific human capital.

Another indirect approach to assess the importance of decentralization of wage formation is to exploit that there are important different implications of how wage formation is affected by taxation depending on whether the market is competitive or imperfectly competitive. While average taxes unambiguously increase wages under imperfect competition, they have an ambiguous effect in competitive markets (income vs. substitution effects). Marginal taxes would under standard assumption increase wage demands in competitive markets and reduce them in imperfectly competitive markets. Using this insight Pedersen and Smith (1999) and Pedersen, Rasmussen and Clemmensen (2002) study wage formation for various groups in the labour market taking explicit account of the more decentralized wage formation allowing a larger role for individual effects on wages. Interestingly, they find that a sample including the first part of the 1990s tends to yield results on the effects of taxation more in line with competitive models, relatively to earlier studies. They take this as evidence that wage formation effectively has become more decentralized.

Interpretations

Can these findings be attributed to decentralization of the wage determination process? The developments in the Danish labour market during the 1990s are a challenge to the literature on the relation between centralization/ decentralization and labour market performance (for a survey and references see Calmfors et al. (2001)). Ranked according to the centralization index Denmark was ranked 4 in the 1970s and ranked 9 in the 1990s for the 15 countries included in the study. Hence, Denmark has moved from centralized/coordinated bargaining to an intermediate position. According to empirical estimates this should imply an increase in the unemployment rate between 3.4 and 6.8 percentage points. If Denmark is interpreted as moving from the intermediate position to the case of low centralization coordination, the unemployment effect is less clear with an effect falling in the interval spanned by an increase of 3.2 percentage points and a decrease of 1.9 percentage points.

A further puzzle in recent developments is that decentralization of wage formation should be expected to enhance the sensitivity of wages to short-run fluctuations in activity, but empirical evidence shows that this has not been the case. One explanation may be that the simultaneous shift in labour market policies has reduced the outside option of workers, which induces wage moderation. Empirically, it is difficult to distinguish this trend shift in market power from the change in cyclical sensitivity over a short sample period.

Accordingly, the Danish experience during the 1990s cannot simply be explained by decentralization of wage formation. This does not mean that decentralization is unimportant, but that it may be interacting with other important changes.

One such change may be that actors in the labour market perceive a different trade off between wages and employment than in the past, due to technological changes and/or international integration. Since the latter two factors have been used in the argumentation for decentralization this is a plausible explanation. In particular the pressure from European integration and the recognition that wage developments different from the “European norm” can be very costly in terms of employment may have moderated wage demands.

However, there are two further arguments related to international integration. First, international product market integration may imply that externalities in wage formation running via e.g. the price level are reduced. Therefore, the relationship between the degree of centralization and labour market performance is muted, cf. arguments in Driffill and van der Ploeg (1993). Danthine and Hunt (1994).

Second, and more fundamentally, international integration may be a separate cause affecting both the institutional structure of the labour market and labour market performance. Product market integration may affect the institutional structure through various routes. Focussing on rent extraction Santoni (2002) shows that a reduction in product market rents (via improved possibilities for reciprocal dumping) following integration implies a reduction in the incentive for both unions and firms to have centralized wage bargaining. Along the same lines Gaston (2002) argues that the improvement in the outside opportunity of firms obtained via easier room for FDIs, outsourcing etc. can explain a shift towards more decentralized bargaining. Product market integration may also increase the costs of keeping wages out of line with productivity since domestic wage formation is less shielded from outside influences the higher various forms of trade frictions. Accordingly, a reduction in trade frictions increases the pressure for having a wage determination system allowing for wages to adjust to productivity, see Andersen (2002) (cf. the changes away from the standard wage system to the minimal payment system). Since this process tends to be accompanied by reductions in bargaining power in labour markets, it follows that decentralized wage formation may be observed simultaneously with improved labour market performance.

During the 1990s there was a gradual change in focus of labour market policies. Traditionally, the policy has been directed toward income insurance. The Danish UI scheme has thus been fairly generous in international comparison (at least for low income groups) and eligibility rules and their administration have been fairly liberal. A sequence of labour market reforms made a change to a more active focus strengthening the requirement of an active search (in particular for young people) and implied that job offers or activation should be offered and accepted much earlier (currently in principle no longer than one year after having become unemployed, and for at least 75% of the unemployment spell of maximal four years for which the entitlement for UI applies). Moreover participation in activation activities does not count for the employment period (at least 26 weeks within the last three years) needed to qualify for unemployment benefits. While there are many open questions concerning the way in which the scheme has been arranged and administrated, it is the case that the reform has lowered the “outside value” of unemployment benefit (can no longer be passively claimed to the same extent as earlier) and this should have a moderating effect on wage formation. Since the replacement rate has not been affected (except for persons below the age of 25) it is difficult to capture the effect of the labour market reforms in standard macro wage models. However, wage equations estimated based on actual replacement rates found that the coefficient to the replacement ratio has been declining during the 1990s (see Bochian et al. (1999)), which is consistent with an upward measurement bias in the outside value of unemployment benefits when the activation scheme is not taken into account.

Concluding remarks

The labour market developments in Denmark during the 1990s have been unique seen relative to the historic experience. This development cannot only be attributed to favourable macroeconomic conditions and a successful stabilization policy. Important institutional changes as well as structural policies have played an important role.

The shift towards a more decentralized wage formation process is one of the most important changes, although some centralized elements remain. This development has taken place against a background of reduced rents to be bargained over (product market integration), improvements in the outside opportunity of firms (via international relocation), and reductions in the outside opportunity of workers (via labour market policy).

An open question in the current situation is whether wage moderation can be maintained despite persistently low unemployment.

References

Andersen, T.M. (2002): Product Market Integration, Wage Dispersion and Unemployment. Working paper.

Bingley, P. and N. Westergaard-Nielsen (2002): Tenure and Firm-Specific Capital. Unpublished Working Paper.

Bocian, S., J. Nielsen, and J. Smidt (1999): SMEC – Modelbeskrivelse og egenskaber. Working paper 99:7. Economic Council Secretariat.

Boeri, T., A. Brugiavini and L. Calmfors (eds.) (2001): The Role of Unions in the Twenty-First Century. Oxford University Press.

Danthine, J.-P. and J. Hunt (1994): “Wage bargaining structure, employment and economic integration”, Economic Journal.

Driffill, J. and R. van der Ploeg (1993): “Monopoly unions and liberalisations of

international trade”, Economic Journal.

Gaston, N. (2002): “The Effects of Globalisation on Unions and the Nature of Collective Bargaining”, Journal of Economic Integration 17, 377-396.

Pedersen, L.H, J.H. Rasmussen and K. Clemmensen (2002): Individual Wage Formation and Minimum Wages: Theoretical and Empirical Effects of Progressive Taxation, Unpublished Working Paper.

Pedersen, L.H. and N. Smith (1999): “Minimum Wage Contracts and Individual Wage Formation: Theory and Evidence from Danish Panel Data”, ch. 6 in T.M. Andersen, S.E. Hougård-Jensen and O. Risager (eds.): Macroeconomic Perspectives on the Danish Economy. MacMillan.

Madsen, J.S., S.K. Andersen and J. Due (2001): Fra centraliseret decentralisering til multiniveau regulering – Danske arbejdsmarkedsrelation mellem kontinuitet og forandring, Fafo Working paper 032.

Santoni, M. (2002): “Product market integration and endogenous bargaining structure”. Paper presented at the IZA Workshop European product market integration and labour market performance.

[20] Defined to belong to the unit interval. A value of 1 corresponds to fully centralized and 0 to fully decentralized bargaining.[]

21 Interestingly, centralization arose as a response to demands from employers.[]

22 Often the agreement is also extended to groups not formally covered by a collective agreement.[]

23 Not to be mixed up with the minimum wage being negotiated, and which sets an absolute floor below, which no worker can be paid.[]

24 Though still firm specific returns play a substantial less role than in e.g. the US.