The DNA revolution has made it possible to use DNA to predict at birth who we will become. This will transform psychology, society and how we understand ourselves, according to professor Robert Plomin, who is a psychologist and behavioural geneticist, currently working at King`s College, London.

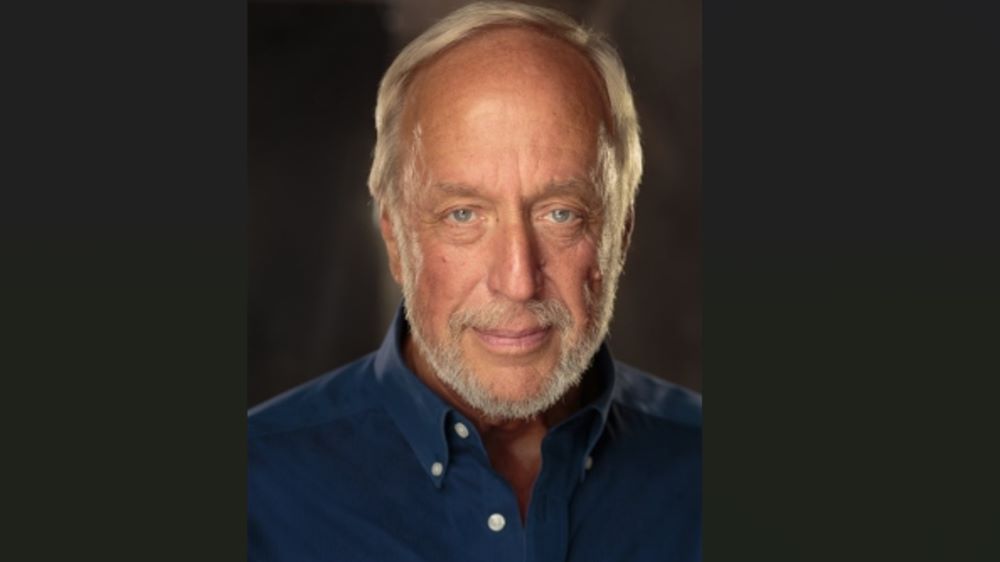

In this e-mail interview Robert Plomin, who is this year`s Eilert Sundt- lecturer, states that he himself is genetically meant to be fat and that parents should relax more and not try to mould children, as if they were a blob of clay.

What has made you spend 45 years studying the DNA?

In Volume 2 of Min Kamp, Karl Ove Knausgård said: “When I was growing up I was taught to look for the explanation of all human qualities, actions and phenomena in the environment in which they originated. Biological or genetic determiners, the givens, that is, barely existed as an option, and when they did they were viewed with suspicion.” Knausgaard’s Proust-like observations of the development of his three children convinced him that they were each very different people from early in life.

I had a similar experience in coming to see the importance of genetics when I was in graduate school in the early 1970s. It might be difficult to believe this now, but back then it was dangerous professionally and sometimes personally to just talk about genetic origins of differences in behaviour.

Psychology at that time was dominated by environmentalism, the view that we are what we learn.

In graduate school in psychology, you never heard about genetics. However, I was graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin where they happened to have the world’s first course in behavioural genetics. I was stunned by early evidence suggesting the importance of genetics. It was thrilling to be part of the beginning of the modern era of genetic research in psychology. Everywhere we looked we found evidence for the importance of genetics, which was amazing given that genetics had been ignored in psychology until then.

We now know that inherited DNA differences account for about half of the differences between people for all psychological traits, from mental health and illness to cognitive abilities and disabilities. I feel lucky to have been in the right place at the right time to help bring the insights of genetics to the study of psychology.

What has surprised you most as a researcher in this field?

Because psychology ignored genetics for so long, I was surprised to discover how important genetics is for all psychological traits. But the biggest surprise for me was what genetics told us about the environment. Two examples stand out.

First, genetic research reveals that most measures of the environment widely used in psychology – such as measures of parenting and life events – show substantial genetic influence, a topic I call the nature of nurture. In other words, what looks like environmental influence – for example, how parents treat their children – is driven by genetic differences between parents and by parents responding to genetic differences in their children. This leads to a new view of the environment, not as events ‘out there’ that happen to us passively, but as active experience in which we select, modify and even create our experiences in part on the basis of our genetic propensities.

Second, studying the environment while controlling for genetics revealed that environmental effects are unsystematic and unstable.

Our experiences with family, school and friends make a difference, but the differences don’t last – we bounce back to our genetic trajectory.

If I understand you right you state that " we would essentially be the same person if we had been adopted at birth and grew up in a different family, gone to a different school and had different friends". Don`t you think that can be quite discouraging for many of us - thinking there is nothing we can do to improve ourselves?

These findings lead to a new view of what makes us who we are. Genetics accounts for most of the systematic differences between us. Environmental effects are important too, but they are unsystematic and unstable. Moreover, what looks like systematic environmental effects reflect us choosing environments correlated with our genetic propensities.

Together, these findings suggest that parenting, education and life experiences don’t make a difference in psychological traits. Parents, schools and friends matter tremendously in our lives but they don’t change who we are.

DNA is the blueprint that makes us who we are.

This is why we would essentially be the same person if we had been adopted at birth and grew up in a different family, gone to a different school and had different friends. This is not hypothetical: adoption studies in which children are adopted away at birth show this to be true.

I don’t think this message is discouraging at all. For example, people are often surprised to find that 70% of individual differences in weight is due to inherited DNA differences. What this means is that some people (me, for instance) find it much easier to put on weight and much harder to lose it. This doesn’t mean there is nothing we can do about our weight.

The DNA revolution has now made it possible to use DNA itself at birth to predict who we will become. In the case of weight, my genetic prediction puts me at the 94th percentile of weight (body mass index, BMI, which corrects weight for height). I am genetically meant to be fat. Does this mean I give up, thinking there is nothing I can do about it? Not at all. I have found this knowledge to be very motivating in my constant battle of the bulge. Also, instead of feeling bad about being at the 70th percentile of BMI, I can congratulate myself for staying far south of my genetic propensity to be at the 94th percentile!

What can the knowledge of the DNA`s fundamental importance teach us as persons and as a society?

Knowing that inherited DNA differences are the blueprint for making us who we are and the new power to read this DNA blueprint from birth is a game-changer for psychology, society and for understanding ourselves. As in the example of BMI, I hope that knowledge of DNA’s importance will teach us tolerance for others and for ourselves.

Genetics, not lack of willpower, makes some people more prone to problems like being overweight, depression and learning disabilities.

I especially hope that this is a liberating message for parents, one that relieves them from some of the anxiety and guilt piled on them by parent-blaming theories of socialization and how-to parenting books. These theories and books can scare parents into thinking that one wrong move can ruin a child forever. Instead, I think parents should relax and enjoy their relationship with their children without feeling a need to mould them as if they were a blob of clay. Part of the enjoyment of being a parent is in watching your children become who they are, as Karl Ove Knausgård so vividly described.