In the Dutch port city, the boats lie close together. On the foredeck of a green-painted schooner, bags and suitcases are thrown into a pile. The crew has already boarded. But not everyone looks equally confident. On the contrary, several of them look up at the tall rigging with worry, while they cautiously stretch out their fingers to touch the coarse ropes.

Soon, the green-painted schooner is making its way out of the harbor. Hege Høyer Leivestad, Associate Professor at the Department of Social Anthropology, stands at the bow looking out over the Wadden Sea. Open sea. The deck sways gently in the swell.

– I must admit that I am quite excited, she says.

Normally, Leivestad researches container ships and ports in the ERC-funded project Ports at the University of Oslo, but today she is acting as facilitator for this voyage, along with anthropologist Elisabeth Schober from the University of Oslo, climate researcher Christiaan De Beukelaer from the University of Melbourne, and Lucy Gilliam from Seas at Risk, an expert on environmental policy.

Leivestad casts a glance at the crew.

– Even though all these people have worked closely with the maritime industry for years, not everyone has been on board a boat.

Six out of nine thresholds crossed

Now they are going to spend three days together at sea. The environmental scientists. The NGOs. The anthropologists and human geographers. Also on board is Josune Urrutia Asua, an artist and illustrator from Spain, who is there to visualize the process. Under cramped conditions, the crew will work to broaden perspectives on the shipping industry. Eighteen people with access to only two toilets. They will share cabins, dine together in the galley, work on deck, pull ropes, hoist sails.

– Most of all, I am eager to see if we can even begin to approach an answer to the incredibly large question: How can the shipping industry contribute to a more sustainable scope of action for humanity in the future? asks Leivestad.

Shipping is responsible for nearly three percent of global climate emissions. Therefore, in 2023, the member states of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) of the UN have set a goal of zero emissions by 2050 – which will entail phasing out fossil fuels in shipping by 2030.

Christian De Beukelaer thinks the IMO's zero-emission vision is ambitious, but objects that it only takes into account one of the seven thresholds for the planet's carrying capacity. Other critical thresholds include loss of biodiversity and the balance of nitrogen and phosphorus. Updated data indicates that we have now crossed six out of nine thresholds.

The situation is beginning to get serious. That's why they are here. On a floating workshop funded by UiO:Energy and Environment.

– It is urgent to phase out fossil fuels on ships to slow down climate change. However, a limited focus on greenhouse gas emissions means that many other challenges are overshadowed, says De Beukelaer.

– Since maritime transport both enables and shapes global trade, it is worth asking what shipping can do to help shape a global economy that operates above the social and economic thresholds of countries and their citizens, while not exceeding the carrying capacity of the planet.

– Since maritime transport both enables and shapes global trade, it is worth asking what shipping can do to help shape a global economy that operates above the social and economic thresholds of countries and their citizens, while not exceeding the carrying capacity of the planet.

Leivestad adds that we as consumers have made ourselves completely dependent on the shipping traffic and the goods it carries on board.

– A huge number of ships sail the world's oceans every single day. Are there other, better, more sustainable ways to organize the maritime flow of goods? asks Leivestad.

– It will be incredibly exciting to see what new perspectives these three days at sea could lead to.

The Earth is not 70 percent water

With enthusiasm, the first-timers compensate for their lack of nautical expertise. Hands unaccustomed to tough tasks eagerly grasp winches, lines, and shrouds. Once the sails are finally up and the schooner is on a steady course, the crew can exhale and go below deck. With flushed cheeks, they settle around the table in the saloon.

Under swaying lamps modeled after oil lamps of yore, human geographer Philip Steinberg from the University of Durham takes the floor.

– The ocean plays an incredibly important role for so many of us. The sea creates connections in the world, for better or for worse, through time and up to today, he says.

But perhaps we also ascribe too much importance to the ocean, Steinberg suggests. In his book The Social Construction of the Ocean, the geographer writes about the importance of being conscious of our relationship to the sea and carefully considering the meanings that we attribute to the maritime.

–- We often hear, for example, that the Earth is 70 percent water. But if you calculate the actual volume of the planet, you'll find that the Earth is really 0.12 percent water. Even at its deepest, the ocean is nowhere near the Earth's core, he says.

Yet the figure 0.12 percent is no more correct than 70 percent, according to Steinberg.

– In some cases, like for a boat that needs to sail from point A to point B, 70 percent might be a more adequate number.

Small places, big questions

The sea is immense, regardless. And Philip Steinberg's point is that we operate with a plethora of truths – a source of both misunderstandings and claims that we shouldn't accept without question.

– Why does have to be so big in order for us to say that it is important? he asks.

Elevated eyebrows over the rim of his glasses.

– Many of the places that are meaningful to us as individuals are, on the contrary, quite small places. Like our homes, says Steinberg.

He emphasizes that we can view the vast ocean as consisting of many small places.

– And I think that's crucial. We mustn't be overwhelmed when we try to tackle seemingly enormous environmental issues. Maybe we shouldn't talk about shipping as a unit at all, but rather break it down into sectors or regions, with their specific challenges? asks Steinberg.

– These are the kinds of things we should be discussing over the next few days.

Play as method

Life aboard the green-painted schooner soon finds its rhythm. The crew alternates between working on deck – with sheets and halyards. And in the saloon – with words and concepts.

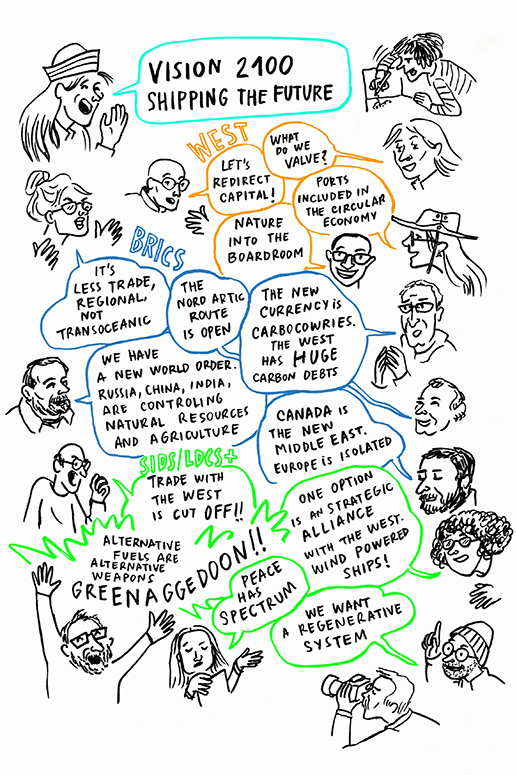

The idea work is underway. Posters, markers, and sticky notes appear on tables. The crew is divided into three groups. Each is to represent the three most important negotiating blocks in the IMO: The West, the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa and from January 1, 2024: Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates), and finally the SIDS – small developing island states – and the LDCs – the least developed countries in the world.

Hege Høyer Leivestad climbs onto a chair and presents the task:

– What will the world look like in the year 2100, folks? What changes have occurred within climate, economy, and geopolitics in your respective areas? And how will the changes affect the future of the shipping industry?

The world in 2100

Heads come together instantly. Hands reach for the colorful markers with the same eagerness as they grabbed the Manila ropes on deck. The humming soon grows dense over the three world coalitions, while isolated words – such as trade routes, south-south coalition, and economic positioning – occasionally flares up.

Leivestad moves between the tables. Thought activity materializes on blue, orange, and green notes. It doesn't take long before future scenarios are drawn to their extremes and back again. Smiles appear on faces, the same red hue in the cheeks.

After a while, Russia has become the only area that possesses fertile soil on the planet, and the Russians have entered into a close alliance with the other new economies, like India and Brazil. Meanwhile, the West has become completely marginalized. Canada is now the new Middle East.

Leivestad comments on the development:

– Some of these scenarios might seem unlikely. But at the same time, if we look back 70 years, we see how much has happened that we could not have imagined. To reflect on possible geopolitical impacts on the shipping industry is absolutely necessary.

Short visit to Brussel

When the groups finally present their visions for the year 2100, the conversation almost takes the form of a parody of a negotiating process – which could easily have taken place between delegates at a formal conference in Brussels.

– I believe that playfulness loosens up the requirement for ideas to be practically feasible and to be based on actual knowledge, says Leivestad.

She emphasizes that the point of the exercise is actually to be as speculative and unrestrained as possible. This paves the way for creativity, the social anthropologist believes.

– And just like that, suddenly, one or two ideas that are not so foolish actually emerge. Creativity is crucial for solving the problems of the future.

What would then happen?

As an example, Hege Høyer Leivestad refers to one group that pointed out the future of shipping will depend on the development in the labor market. How much it costs to produce something in China, for example, and transport it to Europe.

– If we have a more globally equal pay system, this type of trade will not be as attractive anymore, says Leivestad.

She also brings up another suggestion from one of the groups, which was about using taxes and fees to drive change.

– Fifteen years ago, paying for a plastic bag at the store was unthinkable. Today, it's commonplace and helps to reduce our use of plastic, says Leivestad.

– Can we think of the shipping industry in the same way? If you impose taxes not only on the producers of goods but also on those who transport them. What would then happen?

The ultimate question

The creaking of the ropes, the lapping against the hull, the constant feeling of being in motion. Among the reflective forays toward a more sustainable humanity, the crew moves around the boat with ever more familiar movements.

The collaboration is becoming effortless, both above and below deck.

But before they know it, the green-painted schooner is on its way back to the Dutch port city. With the afternoon breeze still in their hair, Christiaan De Beukelaer and Hege Høyer Leivestad attempt a summary of their days at sea.

– It's a bit scary when eighteen people who don't know each other get on a boat and have to stay there for three days. But I think we all agree it's been really pleasant, and that we've had some really good conversations, says Leivestad.

De Beukelaer nods and agrees.

– I think it's amazing how we have managed to establish a space where we can express ourselves freely and playfully, while at the same time being able to shift gears and seriously consider some of the ideas that have appeared precisely because we've been so playful, he says.

But unlike in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the crew has not found a single answer to the ultimate question of how the shipping industry can contribute to a more sustainable world.

– We honestly didn't expect to find it, either, says De Beukelaer.

– Yet, in these three days we've made connections that could be crucial for the important work ahead. And I believe we are now able to ask slightly better questions, which after all is our most important task as social scientists.