“Cod as a species is attached to much commercial interest, and companies are seeing huge benefits to making it breed- and farmable,” Tommas says. Exploring the economization of fishing by way of the digital, he aims at contributing to understanding the role of gene sequencing in research, as well as its participation in the sociology of expectations and the creation of values in innovation projects. “No one knows yet if it will become farmable or not. What I can say is that the cod is proving very resistant,” Tommas smiles.

“Thanks to Little Tools, I’ve gained access to research data from the Aqua Genome project.” The Norwegian research project utilized the latest high-throughput sequencing technologies of the time to generate a comprehensive database of cod and salmon genes. Re-sequencing 1000 individuals of each species translated the fish into their genetic mappings, representing broad ranges of aquaculture stocks, phenotypes and wild populations.

Making Tommas reveal just what it is he is researching isn’t so easy. “I don’t want to get locked in. I’m also more of a collaborator, than a proper member of the Little Tools project. And being only 4 months into it, I do not want to divulge what it is that I’m doing, yet”. Eying his deadline some 3 years from now, he instead rambles on with me about our shared enjoyment of tracked transportation. And we get another coffee.

To understand the future, we look to the past. Several years after Tommas first came to Oslo from his home region of Sunnmøre, and initially leaving a unfinished philosophy degree, he returned to the university. “I had been driving trams for many years, and I understood that I really wanted to do a PhD. For that I needed a master’s, and before that, to finish my bachelor’s.”

Through frameworks of ideas

For his second attempt at being a student, Tommas chose another field: “I soon realized that I had mistaken philosophy for the history of ideas the first time around. Although I enjoyed philosophy, I was truly interested in contextualizing ideas, to see connections and analyze systems of thought, and not judge their inner validity or coherence.”

The combination of methodology from the history of ideas together with experiences from digital humanities has carried into his later work in science and technology studies (STS). Three years later he had the master’s in hand, together with a prize check from the faculty’s “Dare to know” award [Våg å vite-prisen], for excellent writing and challenging established truths.

The combination of methodology from the history of ideas together with experiences from digital humanities has carried into his later work in science and technology studies (STS). Three years later he had the master’s in hand, together with a prize check from the faculty’s “Dare to know” award [Våg å vite-prisen], for excellent writing and challenging established truths.

Tommas identifies a match between him and the TIK centre as a vital factor in the success. “It was like it was made for me, but the academic perspectives of STS was a hard nut to crack at first. By latching on to the concept of ‘interpretive flexibility’ and the Kuhnian notion of science as a craft, I explored the debates to which Thomas Kuhn was responding. This set me up with the basic insights I needed to get a grip on the field. Today when writing, I still reach for this methodology from the history of ideas, its way of articulating the intellectual framework of concern and map concepts. I find it extremely helpful.”

Code repos - research data

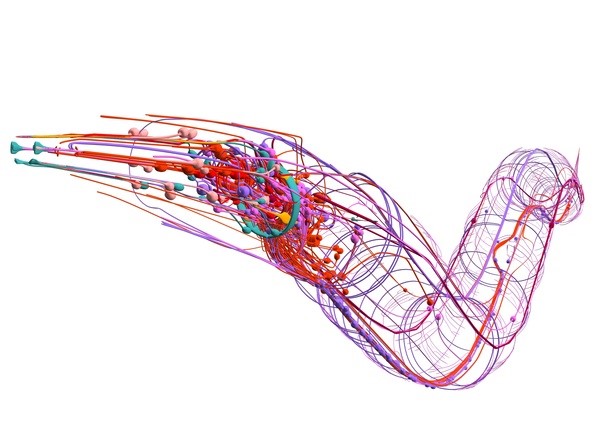

In his master’s thesis Tommas wrote about the OpenWorm project, and their goal to make a connectome, a neurological mapping and simulation of the roundworm, Caenorhabditis elegans. “Doing open source and open science, they published a wealth of materials online, both for recruitment and operational purposes. My data was their working files on Github, and in particular the software documentation. There is a community articulating itself within video conferences and Youtube as well, showing science in the making.”

“It was important for me to treat these sources properly, in the same way one would treat traditional literature,” he says. Following the worm in code and help files, he soon found the roundworm’s trajectory along a path first articulated by AI-researcher Nick Bostrom: From wet technologies in the lab, up into the clouds by way of simulation, transferred back onto the hard materiality of robotics.

Answering his research question of “How does the digital translate into life”, Tommas concluded that:

“[…]as a product of biological exchange, the virtual worm is not able to completely relinquish the petri dish. In order to remain a worm, it must be validated against biological worms.”

The Little Tools project warmly welcome Tommas to the team, and are excited to see the fruits of him applying his methodology on aquaculture sciences.