3.1. Saga

The scene was Saga’s general assembly. The date: May 20, 1998. There was a scent of optimism and expectation in the air. Saga was changing its CEO. Asbjørn Larsen, who had led the company for more than twenty years, was resigning in favour of Diderik Schnitler. Schnitler, who had been recruited from a position in London as senior vice president of Kværner, had taken the new position in anticipation of serving for a long period as the head of Norway’s privately owned oil company.

The results for 1997 were acceptable if not brilliant.[19] The share price was steady and the general assembly voted unanimously for a resolution to combine Saga’s A and B shares and to lift the voting restrictions for the company that had historically served as a protection against unfriendly takeovers. The reason was, according to a press release from the company, “to increase liquidity in the market and better show the values of the firm”.

Seen from the outside Saga had a number of strong points working in its favour:

- Political support for its status as a third independent company was not questioned. None of the investment analysts thought that a takeover/merger was imminent, at least not sufficiently for this to influence their recommendations and the share valuation.

- Saga was an organization of dedicated people. Its exploration department in particular had a good reputation and the way that the company had organized its large development projects like the Snorre field had won praise from the Norwegian offshore supply industry. Furthermore, it had a relatively non-hierarchical structure and was in an organizational sense probably the most “modern” of the Norwegian oil companies.

- In 1996 Saga had undertaken the second largest foreign takeover of any Norwegian company when the company bought the British upstream company Santa Fe for USD 1,2 billion. This made Saga a significant player in the North Sea, with the aim of catching up with Hydro.

But only 13 months after the general assembly of 1998 the situation had completely changed and Saga had ceased to be an independent oil company. Part of the explanation is found in the state of the company itself.

3.1.1. A heavy historical burden

Things were not as good as they seemed. With hindsight a number of weaknesses stood out.

An unrealistic strategic vision for the future: Saga aimed to grow both nationally and internationally and become a “world class” deepwater company.[20] To present a vision that implied that your key competitors were the world’s largest oil companies was at best a miscalculation and at worst indicated a serious lack of realism. The capital and skill requirements that such a strategy required would have been formidable for a company like Saga.

The purchase of Santa Fe: The Santa Fe acquisition of 1996 turned out to decisively weaken the company. This was partly because of the disappointing performance of its new portfolio, partly because of bad timing (or bad luck) with the oil price.[21] Saga’s geologists and geophysicists spent months analyzing Santa Fe’s portfolio and should have given management some warning as to the doubtful quality of part of the portfolio, but they did not. Saga showed its lack of international experience in the actual integration of Santa Fe. It kept Santa Fe’s CEO as head of the new company while showing a lack of cost control when the two organizations were integrated[22].

An unfavourable financial and market position: A comparison of Saga’s key financial indicators with those of Statoil and Hydro and other companies showed that Saga was in a very weak situation. (cf. Tables 3.1 and 3.2). The debt/equity(D/E) ratio is a very good indication of the financial robustness and ability to act of a company. Comparing the debt/equity ratios of Saga with Hydro and Statoil for 1997, Saga was by far the weakest of the three. The increased debt following the Santa Fe acquisition goes a long way to explain this weak position. The return on capital (ROCE) was low compared to that of its peers and costs were higher. The weakness of the company was reflected in how it was viewed by the markets, which valued Saga’s reserves lowest of any ($2,83/bbl), while the company had an expected price to earnings (P/E) ratio for 1999 of 6,9, again at the very bottom of the scale. This was also the case for a third commonly used variable (Enterprise Value (EV)/Debt Adjusted Cash Flow (DACF)) that was expected to be 3,8, compared with an average among European independents of 5,7 and among integrated companies of 8,5.

Table. 3.1 Financial comparison of Saga, Hydro and Statoil (1998)

|

D/E

|

ROCE (98)

|

P/E

|

||

|

Saga

|

1,8

|

3,0%

|

6,9

|

|

|

Hydro

|

0,5

|

8,0%

|

12,5

|

|

|

Statoil

|

1,3

|

4,9%

|

n.a.

|

Source: Goldman Sachs

Table 3.2 Saga compared with a composite of companies

|

P/E

|

EV/DACF

|

|

|

Saga

|

6,9

|

3,8

|

|

Average for US independents

|

22,5

|

5,7

|

|

Average for European independents

|

24,2

|

5,5

|

|

Integrated oil companies

|

18,1

|

8,5

|

Source: Goldman Sachs

Saga’s financial weakness became increasingly clear as the oil price started to decline from the spring of 1998 onwards. (Figure 3.1) Most oil companies have the financial resources to withstand low prices. Saga was less capable of doing this for the reasons referred to above.

(Illustrasjon mangler)

Source: IEA

Fig. 3.1 Oil price development (USD/bbl)

A small and concentrated portfolio: Saga was running its operating fields (Snorre, Vigdis and Tordis) in a relatively efficient manner, but the fundamental problem was that these fields were concentrated in one part of the Norwegian shelf, in the Tampen area. All attempts to establish a new core area outside this area, for example the Haltenbanken area where Saga had made the Kristin find and been a player from the very start, failed as Saga rapidly found itself “locked in” by its much larger competitors. Saga had to enter into a cooperative venture with Statoil to try to compensate for this, and thereby lost the initiative in the Haltenbanken area.

3.1.2. Schnitler’s first months

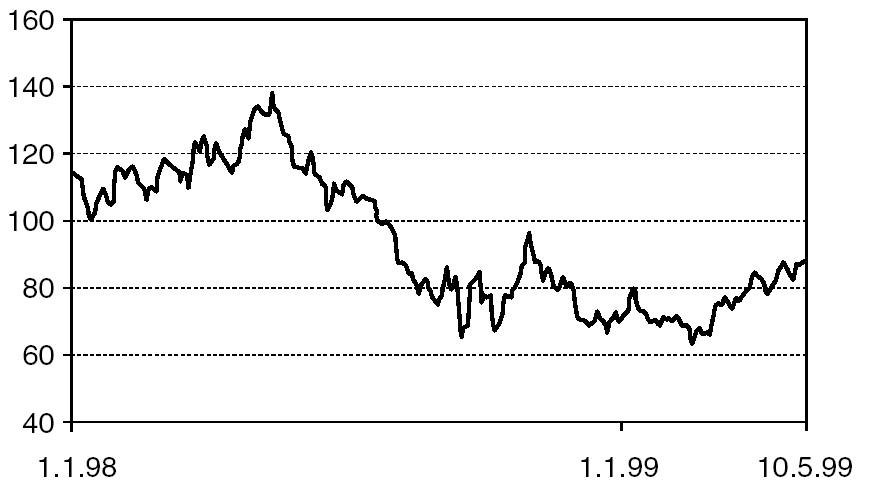

Schnitler did what all new CEOs tend to do: he cleared both real and imagined skeletons out of Saga’s closets. He was quite aware of some of the weaknesses referred to above (he had been in the company since January) and when confronted with a declining oil price he almost immediately issued a profit warning. Saga’s share price started a downward trend (figure 3.2), a dive it was not going to recover from until the following spring.

Fig. 3.2 Saga’s share price development (in NOK)

During the summer and autumn of 1998 Saga’s results steadily deteriorated. Secondly, tertiary results were worse than expected[23]; the Santa Fe portfolio was written down by NOK 2,4 billion, while the oil price continued to slide. Assets were prepared for sale.

Such negative results should not, in themselves, be that worrying. The petroleum business is a commodity business and there are very significant fluctuations in the price level of commodities. Periods of weak or negative earnings are compensated for by periods of good returns.

But Saga’s situation was different. As referred to above, its financial situation was weak and the company had a very expansive vision. If it was to implement this vision it needed access to substantially more capital. Saga could have had a chance to survive if it had simply aimed to harvest the returns from its fields on the Norwegian shelf. But that was not part of its vision and this strategy would not have created any new value for its shareholders.

A very discreet discussion started during the autumn of 1998 among the management and at board level on whether a strategy of “going it alone” was viable. No conclusions were drawn, but doubt was being cast on Saga’s vision to continue forever as an independent oil company. And at the centre of such deliberations was the question: Which strategy would ensure the maximization of “shareholder value”?

3.1.3. The choices

Saga’s shareholders would, at any given moment, compare the likely share price development from different strategic options. Three options stood out:

- “Business as usual” based on organic growth, an option whereby Saga would continue as an independent company.

- Saga entering into different kinds of alliances/joint ventures with other companies, while maintaining some degree of independence. In some forms of alliances there is no change in the corporate governance of the two firms; in others there may be substantial changes in the way in which the two companies are run.

- An outright sale of the company as a block or via an auction of its different assets, for either cash or shares. Such a move could take place following a hostile or friendly bid or by an auction.

- A fourth option – to buy another company – was never on the cards because of the financial weakness of Saga.

Saga’s board and management continuously evaluated these options against each other during the 1998/99 periods. The different options were compared on the assumption that the option that created the highest net present value for the company (the “fair value approach”) would be translated into a maximization of shareholder value.

A recurring theme in both Saga’s administration and its board during 1998/99 was the question of alliances and joint ventures. Was there any linkup with another company that would create more value than the “go it alone” option that was always on the table? Saga had throughout its history been in very close discussions with other companies about possible alliances, but they had all come to nothing. Historically most interest and attention had come from the two French companies Elf and Total, even if both were interested in outright acquisition. Total tried to take over Saga in 1988 but did not succeed. The result instead was that Volvo came in as a new 20 percent owner.

By the autumn of 1998, parallel with an external and internal situation that deteriorated rapidly, it was becoming clear to Saga’s management that a systematic analysis of Saga’s strategic options and in particular the question of alliances, was necessary. The investment banker Goldman Sachs was hired and immediately set to work, concentrating initially on strategic partnerships/alliances. These could take different forms:

- Minority ownership by a partner in Saga.

- Majority ownership by a partner in Saga, but through an industrial solution that would retain Saga and its organization as a distinct entity.

3.1.4. Geographic/international partnerships

By establishing a joint venture for defined geographic areas, Saga hoped to secure a critical mass for its international portfolio, which was too small to secure the required economies of scale.

Such a move was “safe” in as much as it would have little consequence for Saga’s Norwegian position and Saga would continue to be in full control and remain an independent company.

On this basis Saga initiated discussions with the world’s largest independent, Burlington, which had a very strong position in the US, North Africa, Indonesia and the UK. For Burlington such talks were of interest because through a partnership, it would gain a foothold in the Middle East.

These discussions came to nothing, as there was soon disagreement over the valuation of the UK assets in particular.

3.1.5. Merger of equals

As the autumn passed it was becoming clear that it was necessary to consider other and more fundamental alternatives. Both of the two UK independents, Lasmo and Enterprise, were obvious candidates for a merger of equals. The main attraction for Saga was that the company would manage to maintain its independence. Merger of equals is a model whereby the exchange ratio is at or close to the market valuation i.e. there is a limited premium to be paid. [24] This model is often politically and socially more acceptable than a takeover, if the deal is structured equitably. Typically there will be a balanced distribution of board and top management positions between the two companies.

Discussions were initiated with both Enterprise and Lasmo. Saga’s position in comparison with these two companies was good. Its share development was stronger than its two English competitors. Its return on capital (ROCE) was higher, while the debt/equity ratio, at least for Enterprise, was even worse than Saga’s.

Enterprise’s CEO, Pierre Jungles, came to Oslo for talks with Saga. A possible “merger of equals” would be especially attractive for his company because it would acquire a critical mass in the North Sea Basin. The talks centred around three issues that tend to be problematic in any “merger of equals”:

- Valuation: the market capitalization was 1/3 for Saga and 2/3 for Enterprise and thus very far from the rough 50/50 that would have been best for a “merger of equals”. Saga could point to its own calculations of relative enterprise value which were closer to 40/60, but these were just calculations and the lopsidedness in terms of value was a great problem. (cf. Figure 3.3)

- Governance was the second issue of contention: the headquarters of the new company would be in London and Jungles made a very strong point that he wanted to be the CEO of the new entity. Enterprise further pointed to the fact that Statoil was a large (20 percent) minority shareholder in Saga, thus complicating the situation.

- Both of these factors would have some consequence for the third factor: public perception. Given the above points the public perception of the deal would be clear, namely “Enterprise buys Saga”. Saga’s Norwegian identity would be weakened, even if a number of technical activities would be kept in Norway. And, not least, the strategic move would take place without any kind of short-term compensation for Saga’s shareholders.

In summary it was likely that a merger would be “more of the same”, with little prospect of future growth. There would be great problems of governance and no re-rating of the merged company.

It is therefore hardly surprising that the initiative came to nothing.

(Illustrasjon mangler)

Fig. 3.3 Saga/Enterprise: a merger of equals?

3.1.6. A minority position: RWE

During the autumn of 1998 German energy company RWE/DEA approached Saga’s management. The company presented the outlines of a business idea that had a number of attractions. RWE proposed to merge its upstream activities with Saga’s, while creating a gas chain integrated into its own markets in Europe. The proposal also included close cooperation in the field of gas for power. To achieve this, RWE would be willing to take a minority (35 percent) position in Saga. It was assumed that 20 percent would be bought from Statoil and the remainder would come in the form of injected capital from its own upstream company. This solution would give international growth prospects for Saga and leave strategic control in Saga’s hands.

(Illustrasjon mangler)

Fig. 3.4 A possible model for RWE/Saga

It was a deal of a somewhat different nature from a straight upstream merger, which also had some clear attractions for wider Norwegian society. The RWE solution would represent a very significant “marriage” between a major German industrial group and a Norwegian counterpart. Despite the fact that trade between the two countries was increasing, there was at the time surprisingly little direct foreign investment by one country in the other. An RWE/Saga deal could change that.

But there were also a number of potential weaknesses associated with the model:

- The market showed great scepticism towards multi-utilities like RWE, which were priced at a different multiple from upstream companies

- What was in it for Saga’s shareholders? Would RWE sit forever on its 35 percent share or would it in the long run try to take over the majority of Saga without giving a high enough compensation for Saga’s shareholders?

- The synergies were modest (NOK 100 mill./year)

However, both companies worked hard with the idea despite these question marks. A date for going public with the deal was set (December 14, 1998) and the companies started work on a joint communication strategy.

But the discussions broke down, mainly because RWE insisted that Statoil should sell its 20 percent share in Saga[25], thereby giving the official “sanction” of the Norwegian government to the deal. Without this, the deal was dead. In other words, RWE was not willing to behave in any way that would upset the Norwegian government.

RWE had a clear alternative, namely to buy 15-20 percent of Saga’s shares on the open market and thus become a player in the restructuring of Saga from day one, but chose not to exercise this option. When Statoil said “no” to the proposed procedure, (cf. section 3.3 below), and this was combined with a very slow decision-making process in Hamburg, the deal came to a halt.

Discussions with Chevron and Phillips (PPCO) during the autumn and winter, whereby Saga would become the European representative of the two North American companies, also came to nothing. In the autumn of 1998 meetings were held with Total and BP, also with no results.

As the discussions with RWE started to come to a close, Elf made a first offer in December 1998 for the whole of Saga. At a time when the share price was falling towards 70 NOK/share, Elf indicated they could be willing to pay a price of 95NOK/share for the whole company. The offer was unofficial and just an indication. But even so it was of great importance. Any board that receives this type of offer from a serious bidder, while it is actively looking for structural alternatives, must take steps to find out what alternatives exist to the offer that has been made. There is therefore a logic that takes on a life of its own and defines what happens next. In short, who was willing to pay a higher price than Elf for Saga?

3.1.7. An industrial alliance: the Shell option

Contact was established just before Christmas 1998 between Shell and Saga. Yet another kind of partnership was proposed, namely a 50/50 joint venture that would have pooled their production and reserves on the Norwegian Shelf. The name of the company would still be Saga Petroleum and its headquarters would be in Norway. A joint operating/investment committee would run the new company and the chairmanship of the board would alternate. Shell would pay Saga in cash to achieve equality of assets while the new company would give Saga (at terms to be discussed) full access to the technological base of Shell.

(Illustrasjon mangler)

Fig. 3.5 The proposed Saga/Shell structure

All activities outside the Norwegian continental shelf were to be kept outside the joint venture.

Such a structure had some clear advantages:

- It would be a way to increase size and hence reap the economies of scale of a joint portfolio. Shell especially suffered from the fact that its Norwegian continental shelf portfolio did not have sufficient size.

- Saga’s position would stabilize. The payment from Shell for the equalization of assets would be sufficient to regain a healthier debt/equity ratio and the company would get access to a superb technological base.

- The Norwegian identity would be maintained.

However, there were also some question-marks:

- Saga’s shareholders would receive no compensation for what many saw as a de facto takeover. There was a “failsafe” button in the deal to answer such misgivings. To avoid Shell starting to slowly increase its share in Saga, it was decided that if Shell bought as much as one new share in Saga, it would have to make a bid for the whole company. The thinking was that in such a situation there would be an open competition for Saga. The counter-argument was that if this happened Shell would have a clear advantage in any bidding war because the two organizations would have been fully integrated so that any new bidders would be at a clear disadvantage.

- Another argument against the deal was that the governance of the new company would have been very complicated, in particular decisions about new strategic moves and acquisitions.

- The deal would have left Saga’s existing international portfolio out on a limb, with the financial flows from its North Sea activities having been cut.

The discussions reached an advanced stage. There was agreement on the business model; again (as was the case with RWE) very detailed plans were hammered out to communicate the joint venture to the rest of the world. The launch date was set for mid-February 1999.

But disagreement soon emerged as to the valuation and hence the equalization payment for the two parts of the companies. This suited some, especially in Saga, who from the outset of the discussions had been sceptical about the idea. The sceptics claimed that this was just a way to lock in Saga’s shares and that the ultimate result of the exercise would be to sanction a Shell takeover of Saga with limited premium for Saga’s shareholders. It was doubtful that such a proposal would have passed a Saga shareholder meeting. The sceptics drew additional arguments from calculations that showed the deal to be dilutive (i.e. involving a loss of value) and hence not to be recommended.

3.1.8. Towards the end game

By the time Saga presented its 1998 results in February 1999, time was rapidly running out for the company. The results were as bad as predicted.[26] There were no solutions in sight. While the oil price was starting cautiously to rebound from its extremely low level, this was not enough to inspire any renewed interest in the shares, which seemed to be stuck in the low NOK 70s. To add to the negative outlook of the company, Saga also met massive criticism from the market because the company had locked in a future oil price for part of its production. Saga argued that to avoid bankruptcy if prices fell below USD 10/bbl for an extended period of time, the company had to hedge the price. The company defended the move by referring to it as “fire insurance[27]. Hydro later had to pay the full price for this commercial mistake. The total extra cost (foregone income) for Hydro of the price hedging was in excess of USD 100 million. [28] The subsequent criticism of the move also reminded Saga about a basic point for investors. They had taken a position in Saga’s shares exactly because they wanted to be exposed to an oil price risk.

It was during this very bleak period that Diderik Schnitler contacted the CEO of Norsk Hydro, Egil Myklebust, and inquired whether Hydro would have an interest in starting discussions about a sale of Saga to Hydro in an all-share deal. One can only speculate as to the reasons for this move. But the most obvious was that Saga was running out of options and that there were some very solid synergies that could result from a takeover that would benefit Saga’s shareholders[29]. Myklebust did not seem very interested. He presumably thought that the time was not yet ripe for such a move (see also section 3.2 below).

For Saga none of the strategic options seemed to lead anywhere, with the exception of organic growth, an option that the market viewed with great scepticism. But the Saga administration was not passively sitting and waiting for its fate. It undertook a rapid and determined slimming down of the company. The number of employees was to be cut from 1600 to 1200 by 1 July and other costs in the company would be reduced by 250 NOK mill. The organization was simplified and the number of units in the company dramatically reduced. And in case the organic growth option did not produce the desired results and the company should be sold, such a rationalization would also lift the value of the company.

The cooperation with the unions in Saga went well. They saw the extreme seriousness of the situation and cooperated fully, at the same time as Schnitler also actively sought their advice. This was in striking contrast with what the situation had been when Schnitler first took over as CEO, when his first move was to get into a confrontation with his employees. In June 1998, without any kind of prior consultation, he had proposed the outsourcing of a number of functions. This met with extreme anger and frustration from the employees, who saw this as an indication of how the new CEO was out of touch with an existing company culture.

Parallel to the continued slimming down of the organization the management and board of Saga decided to make one new attempt to find a suitable structural solution for the company. A number of companies were approached to see whether they would be interested in making a bid and/or any other kind of proposal to Saga. In April 1999 a set of data were made available at the office of a leading Norwegian law-firm where interested parties could view Saga’s whole portfolio.

Neither Statoil nor Hydro were informed so we must draw the conclusion that this was not a normal “data room” exercise that required the consent of the partners in the different licenses. But there can be little doubt that by now a full sale of the company was one of the options sought by Saga, without excluding any other solution. This was not the first time Saga had made such a move. As mentioned above, Hydro had been approached earlier in the year and Elf had actively been asked by Saga’s financial advisors to make a bid for all of Saga in March.[30]

The knowledge that Saga was actively seeking new partners reached Hydro towards the end of April and served as background information when Hydro decided to bid for Saga on May 10.

3.1.9. The Elf option

After Hydro made its bid, the centre of attention moved away from Saga’s management and board towards potential new bidders. The question was no longer whether Saga would be sold, but rather whether any new bids would be made to increase the final price. Elf, which earlier had shown an interest in Saga and which on 13 April had submitted an indicative proposal to Saga‘s board of directors,[31] now saw its chance to come back and make a public bid for Saga. The Saga board had actively solicited this bid.[32] On 28 May Elf made its move and offered NOK 115 per share in cash for the company. On June 7 the bid was raised to NOK 125 per share. In many ways an Elf/Saga merger was attractive. The model was a total takeover, but with some significant “sweeteners”. Saga was to merge with Elf and operate as Elf’s subsidiary on the Norwegian continental shelf, but under Saga’s name. Elf’s activities in Norway, including its 400 employees, would be integrated into the new company. This would produce a company of sufficient size to operate efficiently. Figure 3.6 shows that a new company would have been number two on the Norwegian shelf in terms of production (SDFI excluded). The official statement by Elf highlighted the potential synergy effects from a merger and indicated a figure of NOK 1 billion[33], which was of the same order of magnitude as the synergies initially indicated by Hydro.

(Illustrasjon mangler)

Fig.3.6 A combined Elf/Saga

Not surprisingly the Saga unions and employees warmly embraced the prospect of an Elf/Saga solution that would have kept their organization intact. It was also very favourably received by the Norwegian media, which emphasized that this solution would maintain the “diversity” on the Norwegian continental shelf (See also section 3.3 below). And there is every reason to believe that the strategists at Elf took into consideration that a takeover of Saga would have strengthened Elf in its expected upcoming confrontation with Total/Fina and would have made a takeover of Elf less likely.

The markets were much less enthusiastic. It was stated in the bid document by Elf that the ROCE for Elf Exploration and Production (E&P) would fall by three percentage points as a result of a takeover. Not surprisingly when the first bid was made, the share price fell. And on the day that Elf pulled back and indicated it would not follow Hydro’s bid of NOK 135, the share price of Elf rebounded. This is the ultimate indication that the market did not believe that Elf would capture sufficient synergies to warrant the offered price.

But in the end it did not matter much. Hydro outbid Elf, to the collective relief of Norwegian politicians who did not have to find ways to block a takeover by a foreign company.

And three months later Total/Fina took over Elf.

[19]Net income increased from NOK 1175 million in 1996 to NOK 1611 million in 1997 and the debt to equity ratio fell from 1,60 to 1,46.

21 The deal was signed when the price was USD 23/bbl; it would give a positive return at USD 18,5/bbl., but Saga encountered prices below USD 10/bbl during the first years following the acquisition.

[22]As an example, Saga chose a very prestigious location for its Saga UK office and refitted it for a total of NOK 350 million. []

23 Net losses amounted to NOK 971 million compared to a net income of NOK 340 million for the same period the previous year. Production declined by four percent. []

24 The 2002 Phillips/Conoco merger was undertaken along such lines.

[ ]25 It offered NOK 103/share for Statoil’s shares, which at the time represented a very good premium.[]

26 The operating loss of the year was NOK 1567 million compared with a profit of NOK 3147 million for the previous year. No dividend was paid and production fell by 5000 barrels of oil equivalent per day (boe/d).

[27] In the end Saga hedged approximately 25 percent of its 1999 production. Saga used two instruments; a price swap whereby the company sold 10 percent of its production for a fixed price of USD 12.01/bbl with an obligation to buy back oil for an average price of 1999 and a price collar whereby the company received a minimum price for its oil in exchange for giving up an upside. The average oil price for 1999 turned out to be USD 18,50/bbl.

[ ]28 Interestingly Hydro did not reverse the positions when they took over Saga.

[29] Schnitler referred in an indirect manner to this offer in a TV discussion on NRK “Redaksjon 21” with Egil Myklebust on May 20. He also made a reference to the meeting in an interview with Dagens Næringsliv (May 11, 1999) where he was quoted as saying that ”one or two months ago there was a meeting with Hydro where the theme was ownership”

[30] “On 24 March 1999, Goldman Sachs International, (Saga’s financial advisor) contacted Warburg Dillon Read (Elf’s financial advisor) and invited Elf to participate in a process for the sale of Saga. See Elf Bid Document, June 1999, p. 12. []

31 Ibid p. 12.[]

32 On May 21 Saga’s chairman Wilhelm Wilhelmsen and Diderik Schnitler met with senior representatives of Elf to discuss a potential acquisition of Saga by Elf. Ibid p. 12.[]

33[ ]Elf Investor Relations presentation, May 1999, p.18.