3.2. Hydro

It would have been almost negligent if the management and board of Hydro had not continuously assessed the possibility of acquiring Saga. The potential synergies following an acquisition were significant. In many ways a takeover could provide a textbook example of how value could be created by combining the portfolios of two companies. Their ownership interests overlapped in most licenses on the Norwegian continental shelf; they shared ownership in pipeline systems, both had built organizations for selling oil and gas into the same markets and their headquarters were in the same city. There was in other words a lot of “cost-synergy” to be reaped – exactly the kind of synergies that the financial markets appreciated. Hydro estimated the potential synergies to be approximately 1000 million NOK per year. This was, however, a pre-tax figure so the real synergies were significantly lower.[34] Probably only Statoil could rival such synergies, even if Elf also made such a claim. At no point did Hydro claim there was a “control premium”, even if the return on capital for Saga was much lower than for Hydro. (cf. Table 3.1). Neither did Hydro claim that there was any “financial optimisation” flowing from the takeover.

But Hydro wanted to take over Saga also for other and more strategic reasons. First and foremost it would provide added size and growth to its portfolio. The elimination of the third Norwegian oil company would also open up the possibility that Hydro would get a larger share of the licenses in upcoming concession rounds.

If it is correct that Hydro historically had been so eagerly seeking a takeover of Saga; why did Hydro sell its 20 percent shares in the company in the autumn of 1998 to Statoil and Hafslund? A number of players, including Statoil and Saga’s management, misinterpreted Hydro’s sale to mean that the company had no further interest in Saga. The sale was, however, a financial move that gave Hydro an excellent return on its investment. That it also could mislead Hydro’s competitors as to their true intentions was presumably an added bonus. Hydro did not have to maintain a 20 percent equity share to keep track of what happened in Saga. The two companies were so close that Hydro had a continuous insight into what happened in Saga, irrespective of its ownership share.

In 1998/99 Hydro faced a number of challenges that further strengthened its takeover appetite for Saga:

- Results were very bad.[35] This was partly due to low oil prices, but also to disappointing results in Norway where the company earned by far the largest part of its income. Hydro’s projects showed serious cost overruns (Visund) and there were few (if any) exploration successes.

- Competition in the industry had sharpened appreciably. A number of E&P companies had merged, were in the process of merging or were being restructured, thus creating more cost-efficient firms. Hydro, it was feared, would be left as one of the few smaller companies, as it was believed that size was a key variable when it came to determining competitiveness

- On the domestic front it was believed that Statoil with its recently launched plans for privatization would become a more serious competitor.

- There was a growing feeling that the low oil price was, if not permanent, then at least here to stay for a long time.

Hydro had launched a large investment programme at the same time as oil prices fell. This led to negative cash flow and there was strong pressure within the company to cut costs. To try to counter the very weak results of 1998 Hydro launched a cost cutting programme named Agenda 99. Exploration drilling was one candidate for cuts and for the first time in its history as an oil company, in 1999, Hydro did not drill a single exploration well as operator.

The financial markets did not show great confidence in Hydro. In the autumn of 1998 Hydro had the greatest proportional share of “sell” recommendations in the market (even more than Saga), cf. Figure 3.7 below.

(illustrasjon mangler)

Fig. 3.7 Recommendations of financial markets

The obvious way forward for Hydro was to grow its portfolio and decrease costs. A takeover of a suitable company would be the perfect way forward. To achieve these aims Saga was – even more than before – the natural takeover candidate. A takeover would increase Hydro’s reserves by 40 percent and its production by 45 percent (cf. Fig.3.8), while leading to synergies in the order of NOK 1400 million as described above.

Fig. 3.8 Consequences of a combined Hydro/Saga (reserves and production)

But despite the weaknesses that Hydro faced, Hydro had two advantages compared to its most important competitor, which was Statoil:

- Firstly, it could use its own stocks as a powerful purchasing instrument while Statoil had to use cash to pay for any transaction. This was almost prohibitive for a company like Statoil, which at the time was in a weak financial situation.

- Secondly, its financial reserves and room for manoeuvring, expressed in its debt/equity ratio, were far more solid than Statoil’s.[36]

The real problem for Hydro was that Statoil had a 20 percent share in Saga and thus an almost de facto blocking interest that Hydro somehow had to deal with .

There was a second reason why Hydro wanted to take over Saga, which went beyond the relative position of its oil and energy division: This was the question of state ownership. Given the importance of state ownership for the development of shareholder value (see section 2 above) and the relatively poor showing of Hydro’s shares,[37] Myklebust and his board had to devise some long-term strategy to lift their share price. Again Saga would be ideal. Since Hydro could pay with shares, a takeover would be a way of watering down the state’s share, decreasing its share from 51 percent to a figure in the mid 40s. This did not represent a final solution for Hydro, but was definitely a move in the right direction. There is reason to believe that for some in the Hydro management this was as important a reason for taking over Saga as what the transaction would mean for its oil and gas portfolio.

But for Egil Myklebust the timing of a takeover had to be right. During the TV debate on April 28 he made up his mind. And on May 10 Hydro made the bid for Saga.

The next question for Hydro was: How much to offer for Saga?

On Friday May 7 Saga shares closed at NOK 85. The offer on May 10 of one Hydro share for three Saga shares meant that the bid was worth around NOK 115 pr share. This corresponded to a 30 percent premium. The Saga board and management had certainly succeeded in exposing the true value of the company. There was little doubt from now on that Saga would be sold. Mr. Myklebust’s strategic move had put Saga in play. The still undecided question was which company would win the contest in the end. There were many potential competitors.

On May 27 Statoil entered the arena and made a joint bid with Hydro. There had been very close discussions between the two companies after May 10. Statoil had made a number of statements that it might make a separate bid for Saga. But in the end it was decided that Statoil would take a 25 percent share of Saga (an extra five percent in addition to the 20 percent they already owned) and everybody assumed that a truly “Norwegian solution” or “business as usual” solution had been found.

But to the surprise of many people, on the following day Elf made a cash bid of NOK 115 that it later raised to NOK 125. On June 11 Hydro and Statoil struck back and made a combined cash and shares offer that guaranteed a share price of NOK 135. The original share exchange ratio was maintained, but in addition there was a cash component worth NOK 4.7 billion or approximately 20 percent of the enterprise value of Saga[38]. Elf then conceded defeat.

Did Hydro pay too much for Saga? Even if there were serious doubts in Hydro at the time that they could defend the NOK 135 offer, the increasing oil price and considerable synergies ensured that the gamble paid off. With hindsight it was obviously a right decision. But at the time the deal was made the markets were very uncertain and part of Hydro’s management was obviously afraid that the price paid would be too high, thus destroying value and sending the share price of Hydro down.

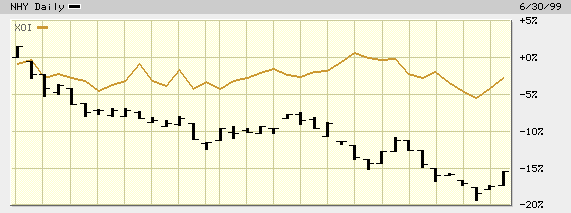

This did not happen. Hydro’s share price hardly moved. On May 10 it actually increased by 0.89 percent in a one off adjustment. Later Hydro’s share price dropped, and the drop was significantly more than the petroleum index of NYSE (Figure 3.9). It is, however, difficult to conclude whether this was a belated “punishment” by the markets because Hydro is a conglomerate where developments of the light metals and agribusiness also influences the share price. Hydro did however admit that earnings per share (EPS) would slightly decrease as a result of the takeover.[39] This indicates that while the markets, from a strictly financial point of view, were not fully satisfied, Mr. Myklebust had clearly managed to carry out a historic move without having been severely punished by the same market – a feat in itself.

Fig.3.9 Hydro’s post deal share development compared with NYSE’s composite oil and gas index

[34] The total synergies were later revised to NOK 1400 million that was broadly in line with the approximately 1000 man years that were saved. The major elements of the savings were “organizational overlaps and efficiencies” (NOK 480 million) and “procurement efficiencies” (NOK 440 million). However because Hydro and Saga were parts of wider consortia these savings had to be “shared” with others. So Hydro ended up only keeping NOK 483 millionout of the NOK 1400 million referred to above. Finally the government taxed the cost gain, so that Hydro ended up with just a fraction of the imputed gross synergies. See Størmer Georg. 2000. “The Saga battle, spring 1999”. Paper delivered in London. January 27, 2000, p. 15. Georg Størmer was Senior Vice President Finance in Norsk Hydro in 2000.[]

35 Hydro’s operating income in oil and energy for 1998 totalled a disappointing 2565 mill NOK that represented a reduction by 60 percent compared with the previous year.[]

36 Hydro’s long term debt divided by shareholders’ equity plus minority interest fluctuated from a maximum of 0,60 in 1994 to 0,37 in 1997. Just prior to the takeover, the ratio was 0,4 compared with Statoil’s 1,3. (See also Table 3.1 above).[]

37 Hydro’s shares as of December 31, 1998 traded at NOK 256/share, the lowest end of year price for five years and a decrease of 29 percent compared to the previous year.[]

38 Saga’s EV was on May 10 valued at NOK 26 bn (approximately half and half debt and equity)[]

39Statement by Hydro June 10 that also highlighted that the cash flow per share (CFPS) of Hydro would increase significantly (“highly accretive”) and that the balance sheet would strengthen despite Saga’s high leverage.